(ThyBlackMan.com) William Holland, a genealogical researcher living in Atlanta, has seen some pretty strange twists in his family tree. Several years ago, he found out that his great-grandfather was a black slave … who wound up serving as a Confederate soldier during the Civil War. But this year Holland’s research resulted in something even stranger.

Thanks to DNA testing, Holland is being welcomed as a long-lost relative by a ruling family of the West African nation of Cameroon. He’s visited the country once already, back in March, and he’ll be getting the royal treatment in November when he goes back with additional members of his family, including his 79-year-old mother.

“Imagine receiving that news, after all these years when you grew up as the son of a sharecropper. … Everybody tells you that you came from slaves, you came from slaves. And now you find out that you came from royalty,” Holland told me.

Holland’s case shows how genetic genealogy can untangle mysteries in a family tree — even for African-Americans, who typically face tougher challenges because the vital records for slaves are so scant.

Holland attributes his success to GeneTree, a Utah-based DNA testing service that came up with the Cameroon connection. But GeneTree’s chief scientific officer, geneticist Scott Woodward, said Williams’ case was far from unusual.

“This isn’t our home run,” Woodward told me. “It takes a lot of regular work. But what [the DNA analysis] did do was give us some nice clues and hints  about where he should concentrate his efforts. Should he be looking in Cameroon, or should he be looking in Nigeria? That makes a big difference.”

about where he should concentrate his efforts. Should he be looking in Cameroon, or should he be looking in Nigeria? That makes a big difference.”

In fact, previous genetic tests had indeed suggested that Holland’s African roots went back to Nigeria — so much so that Holland arranged for some of his supposed Nigerian relatives to get tested as well. “When the results came back, it wasn’t a match,” Holland said. (I can sympathize with that situation: Nine years ago, I went down a similar blind alley in search of my Irish roots.)

So Holland went back to the drawing board. This time, Holland plugged his genetic markers into a database provided by the Sorenson Molecular Genealogy Foundation, which draws upon GeneTree results as well as global genetic surveys.

Unlike whole-genome sequencing or paternity tests, genealogical testing generally looks at only a limited number of DNA markers — either on the Y-chromosome, which is passed down from fathers to their sons; or in mitochondrial DNA, which is passed down from mothers to their children. Such markers can’t be used to figure out your susceptibility to disease or even trace all your relatives. It can only give you an idea who you’re related to along your all-paternal or all-maternal line of ancestry.

The freely available Sorenson database takes the family search to an extra level, by linking the genetic data with traditional pedigrees contributed by those who have been tested. What’s more, Sorenson’s researchers — including Woodward, who serves as the foundation’s executive director — have added test results from places around the world that would otherwise be poorly represented in genetic databases. For example, about 12,000 of the 110,000 DNA samples in the Sorenson files have come from Africa.

“Most are centered in western Africa, because we believe that’s the most interesting, particularly for African-Americans,” Woodward said. “We’ve sampled literally hundreds of different villages throughout these countries.”

In Holland’s case, the best matches all landed in Cameroon. “That’s what got William excited about pursuing and checking some of those places,” Woodward said.

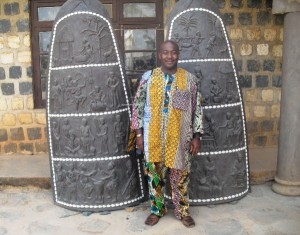

Armed with detailed pedigrees that linked up with the genetic matches, Holland headed out to Bamenda, the capital of Cameroon’s North West Province and the place where the chief of the region’s Mankon people has his palace. Holland discussed his family tree with tribal leaders in Bamenda, and eventually was received by the Mankon chief, His Royal Highness Fo Angwafo III.

“He was so surprised,” Holland recalled. “He gave me about an hour of his time. He looked at me, and he just couldn’t believe it. He told me, ‘William, you could be my son.'”

During the month that followed, local elders pored over all the records that Holland had prepared. Then they called him in to hear the verdict. “With all the pedigrees you show, you belong to the royal family,” Holland said he was told.

Other research has helped fill in the historical gaps: Historians say that only a few ships were involved in the slave trade between Cameroon and Virginia in the early 1770s, the time frame during which Holland’s ancestors came to the colonies. “I think I may have the actual ship that brought us to America. The Cambridge sailed in 1771. The Fox sailed in April 1772. I think that was the one,” he said.

Today, the 41-year-old Holland is working to renovate the family homestead in Virginia, where slaves once lived. He’s also working to get his complete family history in order — and encouraging others to go on their own family quest.

“We all come from different parts of the world, but this is how we come together,” Holland told me.

Meanwhile, Woodward and other researchers are working to develop new genetic tools for tracing family connections. One method would check markers on additional chromosomes to “fill in close relatives, we’re thinking within four to six generations, and reconstruct a relationship between two individuals who share a common ancestor,” Woodward said.

“That’s not even in beta. It’s in alpha,” Woodward told me. “It essentially covers all of your ancestors.”

That could mark a significant leap forward for genetic genealogy. The tests conducted on Y chromosomes or mitochondrial DNA aren’t powerful enough to detemine the precise relationship between two individuals. But when they’re accompanied by hard work and personal contacts, even those tests are clearly powerful enough to forge an ocean-crossing link between an African chief and the son of a sharecropper.

“They’re planning a huge welcome-home party for us in November,” Holland said of his newfound family in Cameroon. “They consider us the lost children. There will be a lot of cooking, a lot of celebrating. … You better get ready. This is something not to miss.”

Written By Alan Boyle

Leave a Reply