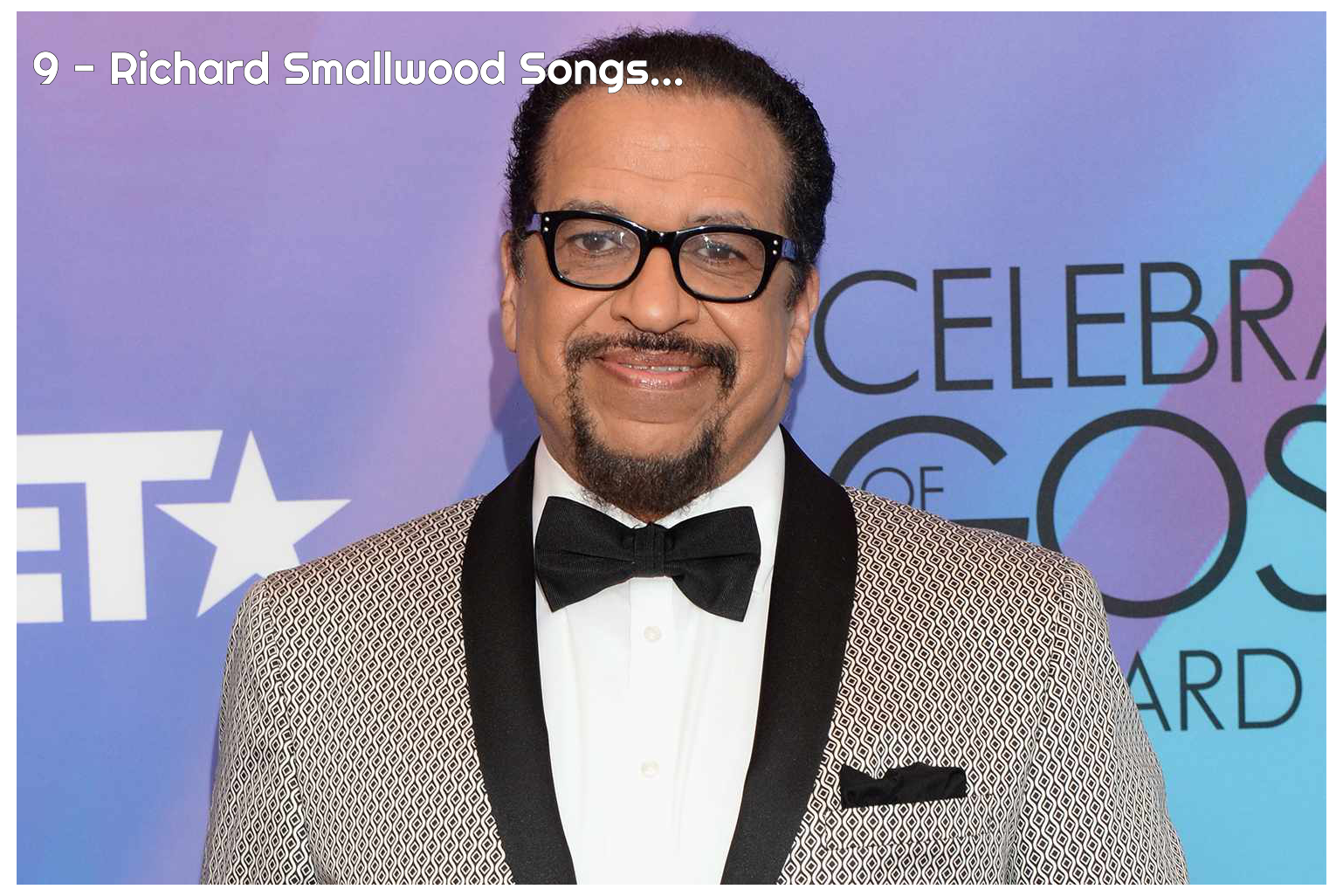

(ThyBlackMan.com) Richard Smallwood was more than a gospel musician. He was a theologian at the piano, a composer who fused classical training with Black church tradition, and a writer whose lyrics carried the weight of Scripture and lived experience. His music did not aim to entertain first. It aimed to minister, to teach, and to endure.

On Tuesday morning, a representative for Smallwood confirmed that the legendary gospel artist passed away due to complications from kidney failure at the Brooke Grove Rehabilitation and Nursing Center in Maryland. His passing marks the end of a physical life, but not the end of his ministry. His songs remain active sermons, still sung in churches, still studied by musicians, and still leaned on by believers navigating grief, faith, and perseverance.

Richard Smallwood’s catalog stands apart in gospel music. It demands patience, attention, and reverence. His compositions were layered, his harmonies precise, and his lyrics uncompromising in their devotion to God. These nine songs represent not only highlights of his career, but spiritual landmarks that continue to guide listeners today.

1. Total Praise

“Total Praise” is not just Richard Smallwood’s most recognized composition. It is one of the most revered gospel works ever written. From its opening piano line, the song establishes a posture of surrender. There is no rush, no spectacle, only reverence. The structure mirrors a prayer that slowly unfolds into full communal worship, drawing the listener inward rather than outward.

Lyrically, the song is rooted in Scripture and personal testimony. Smallwood does not speak in vague spiritual language. He names God as strength, help, and sustainer. Every line builds trust. The repetition is intentional, not filler. It allows worshippers to move from hearing the words to internalizing them, turning confession into conviction.

The composition reflects Smallwood’s classical training and deep understanding of choral dynamics. The chord progressions are deliberate, and the choir arrangement feels architectural in its design. Each vocal part serves the whole, reinforcing unity rather than spotlighting individual voices. The song teaches worshippers how to listen to one another as much as they sing together.

What makes “Total Praise” extraordinary is its emotional discipline. It does not rely on crescendos for impact. Instead, it invites patience and stillness. That restraint allows the song to meet listeners in moments of grief, gratitude, or reflection without overpowering them. It becomes a shared language for faith across denominations, generations, and circumstances.

As long as people seek refuge, stability, and assurance beyond themselves, “Total Praise” will remain a sacred point of reference in gospel music.

2. I Love the Lord

“I Love the Lord” captures a deeply personal declaration of faith. It is worship stripped of pretense. Smallwood’s lyrics echo the Psalmist’s gratitude for a God who hears cries and responds with mercy. The song feels intimate, almost confessional, as if listeners are being allowed into a private moment of gratitude.

The melody moves gently, giving space for reflection and honesty. There is no pressure to impress or perform. Instead, the song encourages vulnerability. Smallwood acknowledges that love for God is often shaped through struggle, through moments when help arrives just in time.

The arrangement is intentionally restrained. The piano and choir never overpower the message. Instead, they serve as witnesses, affirming the testimony being spoken. This careful balance reveals Smallwood’s sensitivity as both a composer and a minister, understanding when to step forward and when to step back.

What gives the song its lasting power is its truthfulness. It does not promise an easy path or instant relief. It simply bears witness to deliverance. Many return to this song after personal storms because it validates survival without glorifying suffering.

“I Love the Lord” continues to resonate because it speaks to faith that has been tested and proven, not faith that has gone unchallenged.

3. Jesus You’re the Center of My Joy

“Jesus You’re the Center of My Joy” functions as both confession and correction. It places Christ at the core of life’s meaning, stripping away distractions and misplaced priorities. Smallwood’s lyrics make it clear that joy does not originate from circumstances, success, or approval, but from spiritual alignment.

The arrangement moves with intention, expanding and resolving in a way that mirrors trust. The harmonies swell and retreat, reinforcing the idea of Christ as an anchor amid shifting conditions. Smallwood’s classical influence is present in the careful pacing and thoughtful modulation.

The song speaks directly to believers navigating loss, disappointment, and unanswered prayers. It reframes joy as something deeper than happiness. Joy becomes rootedness rather than emotion. That distinction allows the song to minister without denial of pain.

What makes this piece endure is its clarity. It refuses to dilute the message for accessibility. Instead, it invites listeners into maturity, reminding them that faith is not sustained by feelings alone.

In a culture that often confuses joy with visibility or affirmation, this song offers grounding and perspective that remain spiritually necessary.

4. Hebrews 11

“Hebrews 11” stands as one of Richard Smallwood’s most intellectually rigorous and spiritually demanding compositions. Rather than summarizing faith in emotional terms, the song defines it. Drawing directly from Scripture, Smallwood treats faith as substance and evidence, not feeling or impulse. The result is a piece that teaches as much as it ministers.

The structure of the song reflects its subject matter. It unfolds deliberately, almost academically, allowing the weight of the text to settle. There is no rush to resolution. The choir moves with measured confidence, reinforcing the idea that faith is not reactionary, but grounded and assured. Smallwood’s classical discipline is evident in the careful pacing and balance between voices.

Lyrically, “Hebrews 11” refuses simplification. Smallwood trusts the listener to engage deeply with the text, resisting the temptation to paraphrase Scripture into something more comfortable. This respect for the Word gives the song its authority. Faith is presented as active trust in what cannot yet be seen, a concept that challenges both intellect and spirit.

What makes “Hebrews 11” endure is its refusal to cater to emotional trends. It calls believers to maturity, reminding them that faith is not sustained by sight, circumstance, or confirmation. In worship settings, the song functions as instruction set to harmony, grounding congregations in biblical truth while reinforcing trust in God’s promises.

As part of Richard Smallwood’s body of work, “Hebrews 11” exemplifies his commitment to gospel music that educates, strengthens, and anchors belief. It stands as a reminder that worship can be both reverent and intellectually demanding, without sacrificing spiritual depth.

5. Calvary

“Calvary” reflects Richard Smallwood’s ability to engage deeply with the foundation of Christian faith. The song is contemplative rather than performative. It approaches the crucifixion with reverence, allowing listeners to sit with the gravity of sacrifice rather than rush past it.

The arrangement builds gradually, honoring the emotional weight of the subject. The harmonies are solemn and restrained, creating an atmosphere that feels almost sacred. Silence and space are used deliberately, reminding listeners that not every truth needs volume.

Lyrically, Smallwood centers the cost of redemption without sensationalism. The song does not dramatize suffering for effect. Instead, it invites reflection, repentance, and gratitude. It respects the listener’s capacity to engage deeply without coercion.

What makes “Calvary” essential is its honesty. It refuses to skip the cross in favor of celebration alone. By doing so, it preserves the integrity of the faith narrative and grounds hope in sacrifice.

In worship spaces that often emphasize victory, “Calvary” restores balance by reminding believers where redemption truly began.

6. Anthem of Praise

“Anthem of Praise” stands as one of Richard Smallwood’s most commanding compositions, blending worship with theological clarity. The song does not build gradually toward praise. It begins already grounded in reverence, as if assuming the listener understands why praise is necessary. There is an immediate sense of order and authority, signaling that this is not casual worship, but intentional declaration.

The structure is expansive, designed for choir and congregation alike. Each section builds upon the last without overpowering it. The harmonies are firm and declarative, reflecting collective faith rather than individual expression. This is worship as communal testimony, where voices move together in agreement rather than competition. Smallwood understood how to write for the church as a body, not just for soloists or recordings.

Lyrically, the song affirms God’s sovereignty and faithfulness without embellishment. Smallwood avoids poetic excess, choosing clarity over flourish. Every line reinforces purpose, reminding listeners that praise is not emotional release but acknowledgment of God’s authority. The language is direct and unambiguous, leaving no room for confusion about who is being exalted and why.

What elevates “Anthem of Praise” further is its discipline. The song resists the temptation to dramatize worship. There are no unnecessary vocal runs or exaggerated shifts meant to stir reaction. Instead, the power comes from unity and conviction. This restraint gives the song longevity, allowing it to be sung repeatedly without losing its gravity.

In worship settings, the song functions almost like a declaration of faith spoken aloud. It gathers the room, centers attention, and reminds participants of their shared purpose. The choir becomes less a performance group and more a vessel through which doctrine is affirmed. That collective posture is what gives the song its commanding presence.

“Anthem of Praise” continues to resonate because it restores balance to worship. It centers God rather than circumstance. It teaches that praise is not dependent on outcome, emotion, or season, but on recognition of who God is. In that sense, the song serves as both worship and instruction, reinforcing Richard Smallwood’s legacy as a composer who wrote not just songs, but enduring statements of faith.

7. Trust Me

“Trust Me” addresses one of the most difficult truths in faith. Trust is not passive. It requires release. Smallwood does not sugarcoat this reality. The song acknowledges hesitation, weariness, and the frustration that comes with waiting. Yet it never abandons the call to move forward.

The pacing of the song mirrors the spiritual struggle it describes. Nothing resolves too quickly. The music holds tension long enough for the listener to feel the weight of the question being asked. This restraint allows the message to settle rather than overwhelm.

Lyrically, the song speaks with pastoral sensitivity. It does not scold uncertainty or doubt. Instead, it recognizes them as part of the journey. The call to trust is presented as an invitation, not a demand. That approach gives the song credibility and compassion.

Over time, “Trust Me” has become a companion piece for believers navigating seasons of silence or delay. It does not promise clarity. It offers presence. That distinction makes the song enduring, especially for those who understand that faith often unfolds without explanation.

Leave a Reply