(ThyBlackMan.com) The Grand Ole Game will never be the same!

As a freelance journalist and an Associate Editor, I will borrow words from two great sportscasters/analyst to describe my elation upon hearing of the merging of MLB and the Negro League statistics: Jack Brickhouse…Hey Hey! Harry Carry would say…Holy Cow!

As a lifelong baseball obsessive, I’ll admit—the news Major League Baseball (MLB) would fold Negro League stats into its hallowed records gave me full-body chills. See, for far too long, those towering talents got shunted off into the shadows, their mind-boggling brilliance obscured by systemic racism. But no more! With this bold, belated merger, the sport I cherish so dearly finally rectifies an egregious injustice, hauling immortal legends like Josh Gibson from undue obscurity into their rightful, resplendent spotlight.

Sure, skeptics always grumble this purposeful rewrite of history’s pages, melding long-segregated stat lines, rewards falsehoods about the past. They bemoan MLB can’t fairly pit apples against oranges—or in this case, white pro ballers flourishing under vastly different, privilege-steeped conditions against their endlessly persecuted Negro League counterparts. An understandable contention on its surface.

Yet I counter that baseball’s abhorrent color line itself radically warped an equitable comparison of greatness back then. Doesn’t making amends for that grotesque stain on our beloved national pastime—while admittedly imperfect—still feel like a worthy endeavor, long overdue? And anyway, make no mistake: Those diamond giants barred from white leagues could absolutely rake, no matter the obstacles.

Undeniable Talent, Unmatched Obstacles

Need proof? Just look at the torrid, sublime pace those African American trailblazers—finally welcomed to MLB in the wake of Jackie Robinson’s 1947 debut—rapidly accumulated major awards and milestones. Within two decades of integrated play, Black superstars like Hank Aaron, Willie Mays, Ernie Banks and Frank Robinson regularly smashed records and corralled MVP awards annually. A prodigious output made even more staggering considering the top-tier level of competition they faced.

This sudden, spectacular confluence of African American greatness simply cannot be overstated—not when you ponder the talent panorama alongside legendary contemporaneous white icons like Mickey Mantle, Willie Mays, Yogi Berra, Duke Snider, and Stan Musial, among countless other immortal sluggers and flamethrowers standing athwart that very same rarified summit. For those newly arrived African American stars to not only reach that peak, but sustain remarkably consistent production befitting inner-circle all-time greats? It boggles the mind…and reinforces just how much preternatural talent was bottlenecked within the long-segregated Negro League realm before at last being released upon the “white” majors.

Both firsthand anecdotes from those who witnessed the blackball circuit at its zenith and rigorously researched modern statistical analyses support this notion: The Negro Leagues consistently fielded ultra-elite athletes whose skills could’ve translated mightily within MLB—lacking only the opportunity denied by the color of their skin. The comparative numbers, whenever possible to accurately cobble together from spotty available data, absolutely back it up.

Like, how mind-bendingly, supernaturally sweet must Josh Gibson’s prolific power stroke have been for the awestruck “Black Babe Ruth” label to stick? Satchel Paige, the ageless rubber-armed wonder, bamboozled batting deity Ted Williams’ razor-sharp eye at Fenway all the way into his mid-40s with everything from rising blazing heat to his trademark hesitation pitch—just imagine the unholy arsenal of electric stuff that mythical right arm unfurled upon flailing white and blackball bats alike during his prime? Old-timers from that long-segregated era consistently ranked, revered and placed titans like Gibson, Paige, Oscar Charleston and Pop Lloyd as the absolute crème de la crème—even when stacked against contemporaneous white ball immortals like Ruth, Gehrig, Walter Johnson or whomever else.

And as previously mentioned, this speculation about those Negro Leaguers’ potentially transcendent talents feels bolstered by the ever-expanding reams of data and rigorous statistical dissection we’ve seen from historians in recent decades. Several laborious studies cross-leveraging all available numbers, first-hand contemporary accounts and other granular documentation have consistently concluded the elite competitive level across Negro League baseball reached authentic major-league caliber more often than not—with upper-echelon performers like the Paynes, Gibsons and Coopers routinely meeting or exceeding the output of MLB’s top players of their time. An incredible, eye-opening accomplishment—especially when weighing the immense roadblocks those blackball pioneers endured every single day out there.

A Grueling, Pioneering Path

Just ponder the arduous, eternally undermining circumstances facing Negro Leaguers at their “peak” for a moment: Those barnstorming, nomadic squads perpetually scrambled for essentials like adequate buses, lodgings, uniforms and equipment—all amenities white MLB organizations took for granted. The sparse, dilapidated accommodations on those endless, grueling road trips—if they could find any establishments at all willing to host black athletes—frequently amounted to dirt-floored boarding houses infested by cockroach squadrons, where exhausted players desperately crashed for a few hours’ rest before reboarding that rickety bus and moving on.

Meanwhile, games themselves frequently devolved into full-on riotous affairs for those Negro Leaguers. Riled-up racist mobs felt free to barrage their heroes with verbal and physical projectile assaults over the grandstand—batteries, liquor bottles, slurs, you name it—while venue officials turned a willfully blind eye at best. Horrendous, viscerally appalling episodes that modern baseball fans can scarcely fathom from our cozy seats today.

Financial woes compounded those ceaseless indignities too. Negro League squads might pack historic venues like Illinois’ Comiskey Park to the absolute gills during marquee exhibition tilts against an MLB opponent’s roster—only for their shady Caucasian promoters to fleece them, stiffing the blackball players from receiving their rightfully owed cut of the gate earnings. Heck, many unscrupulous Negro League owners themselves notoriously skimped on covering even the most basic necessities like fresh uniforms for their exploited players, that’s how tightly budgeted money ran.

So while immortal icons like the sweet-swinging, acrobatic Charleston, Cooperstown-worthy masher and receiver Gibson and indefatigable iron man hustler Cool Papa Bell routinely displayed their supernatural talents between those distant chalked lines—they did so under physical and psychological conditions that could shatter even the most grizzled, resilient person’s spirit. Decrepit, vermin-infested facilities, hateful slur-spewing throngs, penny-pinching owners balking at basic human dignities. All amid the broader, pervasive shadow of Jim Crow, threatening to upend their very existence off the diamond at any moment.

And again, through it all, those players soldiered forth with the suffocating knowledge that for all their matchless on-field feats—the true “big leagues” and recognition as society’s athletic elite remained an eternally inaccessible, forbidden fantasyland denied them solely by the melanin content in their skin. A cruelty seemingly designed to crush even the most buoyant athletic dreams and sharpest competitive instincts in every childhood.

Yet conquer they did, dominating at the highest possible levels while segregated from baseball’s competitive apex. An almost philosophical fortitude emitting from that steadfast refusal to succumb or be broken—their collective willpower granting permission for individual greatness to flourish wherever the game happened to be played. It strains conventional belief about the limits of human resilience and speaks to their utter, immortal athletic transcendence as all-time talents.

And maybe that’s the clearest window into why those Negro Leaguers stood apart: In addition to their prodigious skills, these ballplayers wielded an immense, nearly metaphysical reserve of character forged from overcoming quite literally everything thrown their way—both on the field and within society itself. We haven’t seen a confluence of mental, physical and spiritual fortitude nearly that resolute since.

“Get Over It”? Nah, I’m Good!

Which is why, whenever I encounter some online troll or hear a radio caller sneer something unserious like “Get over it already! This was nearly a century ago!”—I have to shake my head.

Those overwhelmingly privileged edge lords hurling thoughtless rebukes from atop pillars of historical ignorance and societal comfort have clearly never once walked the treacherous, trauma-dotted mile in those Negro League icons’ trodden shoes. Each demeaning slight, every openly hostile custom and ritual, all the constant micro (and macro) aggressions steadily inflicted upon those Negro Leaguers by society—those accumulated insults and indignities only intensified their daily toil into an entirely separate, scarcely fathomable realm of normalized struggle foreign to us all today.

Which is precisely why MLB choosing to finally, earnestly recognize those pioneers’ elite statistical accomplishments within its official hallowed record feels so vital—a long-overdue corrective helping restore at least some semblance of lost dignity.

Do I still believe incorporating Negro League stats into MLB’s record books holds some imperfections or creates potentially imprecise 1:1 player comparison across vastly different eras and conditions? Of course—that much feels inescapable given the varying record-keeping methods, quality control practices and competitive contexts from that bygone, under-resourced age of deplorable segregation. Some gray areas, minute discrepancies or straight-up gaps in documentation are inevitable when cobbling together historical info across such disparate times and circumstances.

But honestly, those unavoidable quibbles ultimately feel downright petty when scrutinized against the bigger picture here: Major League Baseball is finally taking meaningful, long-overdue action to make institutionalized amends for its sport’s shameful, grotesquely racist segregation edifice that subjugated so much transcendent talent for generations. A symbolic reckoning with the harsh truth that yes, elite African American athletes could definitively hang at the highest level—and indeed, often surpassed their white contemporaries’ hallowed production, despite overwhelming odds.

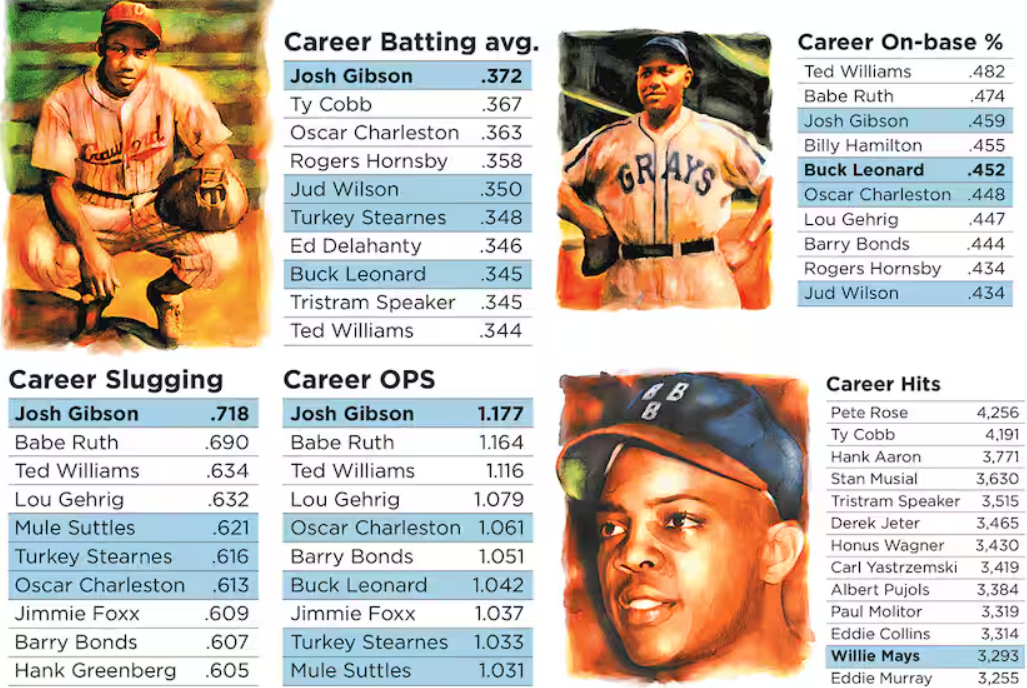

By absorbing those neglected Negro League stat lines into its official canonical records, including Josh Gibson’s eye-popping .441 lifetime batting average—far eclipsing the great Ty Cobb’s formerly recognized .366 MLB mark—the sport finally turns a crucial cultural page toward reconciling its abhorrent, subjugating past baked into those very same record books. Numerical revisions that help reframe how we contextualize the whole of baseball history through a more equitable, accurate lens.

And to me, that bigger-picture symbolism and reckoning feels about so much more than the cold, flat impersonality of mere batting averages, pitcher win-loss records or other career counting stats anyway.

More Than Numbers

We’re talking about hallowed ambassadors and folk heroes like Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson here—titans who embodied hope, human dignity and resilience through athletics, serving as emblems for that eternal striving toward excellence that lies within all our spirits, no matter our race or background. Beacons of black American heritage whose very existence sparked embers of belief, even among the oppressed masses denied their MLB-level talents.

So to simply dismiss those legends’ mind-boggling statistical outputs as somehow invalidated or incompatible because the conditions of their time proved imperfect feels almost insulting to their collective significance. We’re not just talking about evaluating Josh Gibson’s career numbers in relation to Babe Ruth’s here—we’re wrestling with how to properly enshrine ambassadors for an entire race’s aspirant trajectories.

Segregation’s open wound deprived so many African American families, communities and kids from seeing their own represented at the highest athletic levels, celebrated and unconstrained in society. Having their limitless potential recognized and validated on the national stage, rather than swept under the rug or sidelined to some peripheral “other” experience, meant something indescribably profound.

So dismissing the Gibson’s and Paige’s astounding exploits and preternatural talents as unworthy of MLB’s official pages due to inconsistent data or competitive separations feels reductive at best—prioritizing stat-keeping minutiae over an entire people’s symbolic struggle for fundamental societal equity and human affirmation through sport. An ironic deprivation baked right back into the supposedly remedial record overhaul.

Which isn’t to say those arguing for a more clearly delineated statistical separation between MLB and Negro League numbers lack intellectually solid ground to stand upon. Issues around competitive imbalances, differing equipment, ballpark dimensions, and other external factors absolutely muddy any true apples-to-apples player evaluations spanning that divide. Doubts remain over record accuracy and data completeness for Negro League numbers too given scant resources compared to their MLB counterparts.

Even if we accept the top-line numbers at face value as major-league caliber, caveats galore exist potentially deflating the most breathless statistical comparisons between top-tier Negro Leaguers and their enshrined MLB contemporaries. Those are all reasoned perspectives worth mulling over and taking seriously.

Honoring History’s Ambassadors

However, continuing to relegate Negro League achievements to a separate, de facto “minor league” realm within the game’s narrative opens way for those accomplishments to remain marginalized in mainstream consideration—ghettoizing those icons’ rightful places among the immortals, purely over racial lines once again. And that perpetuates the very sins of exclusion MLB now aims to symbolically correct.

Jackie Robinson himself said it best: “A life is not important except in the impact it has on other lives.” And by that immensely meaningful metric, Negro League icons like Josh Gibson and Satchel Paige left an overwhelming, multi-generational impact upon us all—regardless of race, creed or birthright. Their perseverance, talent and sheer black excellence championed human decency through the athletic arena during an era when bigotry and hate remained inextricably enshrined across American society.

We remain in their debt for embodying those displays of courage and resilience that resonated deeply with the downtrodden, reminding all human spirits of their own vast potential awaiting actualization. Their significance stretched far beyond the stadiums they circled or box scores they authored.

Which is why, despite some inevitable handwringing from stat purists or those outwardly peeved over surface-level “historical rewriting,” I wholeheartedly celebrate MLB’s decision to finally merge that hallowed history and those immortal numbers beneath its official umbrella.

While the integration admittedly creates some legitimate record-keeping quirks and gray areas for studious analysts to wrestle with—the symbolic value of enshrining those subjugated legends ultimately supersedes any imperfections in execution. More importantly, it broadcasts this truth to all: Those Negro League greats may have been shuttered from America’s white-dominated mainstream culture and banished to the periphery of society at the time…but their immortal, inspirational impact looms just as large within baseball’s human storyline as anything achieved between the chalked lines of the biggest MLB stadiums.

Going forward, young fans will behold Josh Gibson’s gaudy .441 batting average and his unfathomable 800+ home runs rightfully ensconced beside Ruth, Aaron and Bonds in their record books and classroom lessons. They’ll encounter Pop Lloyd’s wizardry documented equally to Mantle’s or Mays’. Oscar Charleston’s accolades will leap off the page with the same authority as Joe DiMaggio’s or Teddy Ballgame’s. Satchel Paige’s ageless feats won’t get relegated to some meager, easy-to-overlook sidenote.

That’s an immensely powerful pedagogical dynamic, both for educating on baseball’s fraught-but-essential racial history and inspiring today’s generation to find their own inner fortitude within that inherited resilience. To remind all that athletic brilliance can be subjugated and marginalized over hideously unjust superficial qualities—but it cannot, will not be extinguished by myopic hatred. Not if icons like the Negro Leaguers persevered in elevating those talents to the level of folk art in the face of overwhelming, institutionalized suppression.

So let the stuffy purists and aggrieved reactionaries grumble over statistical minutiae or bemoan imaginary “rewriting” of pristine history all they want. Ultimately, absorbing those segregated pioneers and their hallowed accomplishments into MLB’s all-encompassing record books solidifies a moral, philosophical, and spiritual maxim more crucial to baseball’s full story than any single career batting average could ever convey:

Those short-sighted enough to systematically exclude any individual’s potential over superficial characteristics like skin color only ensure the permanent sightline of their own ignorance remains obstructed from witnessing transcendent human brilliance.

Put more simply, as a wise writer once summarized: “All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players.” Well, the likes of Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige, Oscar Charleston and so many Negro League ambassadors were all-time thespians performing their roles on baseball’s grandest stages—even if the curtain did discriminately rise upon them then. It’s about time their iconic numbers, statistics and historical prominence got a permanent spotlight as well.

Associate Editor; Stanley G. Buford

SGB is a prolific author with 36 books to his name. His works include notable titles such as The Truth About Tee’s Tooth: A Rhyming Story, The Infant Mortality Rate and the Black Community, and Thanks Dad!.

Currently, he holds the position of President at Terkat Consultants Inc. and serves as the Executive Director of the From Boys to Men Network Foundation Inc. His extensive experience and dedication to his field are evident in his ongoing contributions and leadership roles.

Feel free to connect with Stanley G. via Twitter at StanleyG and on Facebook at facebook.com/sgbuford. He can also be reached by email at StanleyG@ThyBlackMan.com.

Leave a Reply