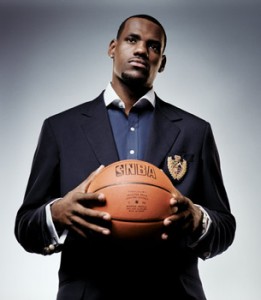

(ThyBlackMan.com) A close examination of the Heat’s LeBron James and the role of race…

Trying to avoid writing about the Miami Heat this season will be as difficult as trying to avoid writing about race and the NBA. Here we are, mere days after the teams assembled for the first time, and already the two inescapable subjects have converged into a sports topic so consuming that we managed to go an entire 24-hour cycle without talking about the New York Jets.

Race is so incendiary that the fire quickly engulfed what should have been the real news emanating from Soledad O’Brien’s CNN interview, namely the first mea culpa of any kind from LeBron James’ camp regarding “The Decision.”

“The execution could have been a little better,” Maverick Carter said. “And I take some of the blame for that.”

When I threw that quote on Twitter all it did was make some people even angrier because Carter couched his confession.

“Mav took ‘some’ blame? SOME?!” @dgoldstein79 tweeted to me. “He’s now up for 2 awards: Worst PR decision of the century AND biggest understatement. Congrats!”

No one bothered to parse the racial comments in the same way. How many people noticed that Maverick used the same “s-word” — some — in addressing the racial component of the summer-long backlash against LeBron?

“It definitely played a role in some of the stuff coming out of the media, things that were written for sure,” Carter said.

It’s important to keep in mind that he and LeBron were merely responding to questions. What O’Brien was doing asking them in the first place is another  matter. For all we know she could have been trying to gather some sound bites for her next “Black in America” special. She asked and LeBron answered, and according to the transcript, it went as follows:

matter. For all we know she could have been trying to gather some sound bites for her next “Black in America” special. She asked and LeBron answered, and according to the transcript, it went as follows:

O’BRIEN: “Do you think there’s a role that race plays in this?”

JAMES: “I think so, at times. It’s always, you know, a race factor.”

That’s all it took. He didn’t claim to be a victim of racial persecution, he didn’t call for a racial revolution. He simply responded to a question and noted that race is a factor at times.

It’s a simple, fundamental truth in our society and, in particular, the NBA. As long as the NBA features predominantly black athletes playing for predominantly white owners who are selling their sport to predominantly white ticket buyers, there will be a race factor. It’s an ongoing quandary, usually left unsaid.

Every once in a while the league will try to address it, never more awkwardly than the “Love It Live” ad campaign that utilized dead white singers as a means to sell tickets to see living black basketball players. Apparently the league felt Elvis Presley and Frank Sinatra made better spokespeople than Kobe Bryant and Shaquille O’Neal. And for the demographic that buys the bulk of season tickets and luxury suites, they very well could have been right.

That brings us to an essential component we must understand when it comes to any discussion of race and the NBA. It’s OK for people to root for people who bear the most resemblance to themselves. I had no qualms with white Boston Celtics fans who bypassed racks of Kevin Garnett and Paul Pierce jerseys to buy a Brian Scalabrine jersey. If they could identify more with him — to the extent almost anyone can identify with a 6-foot-9 man with OrangeSicle-colored hair — that’s fine. It’s no different than black people who previously didn’t care about the difference between a serve and a volley rushing to the TV to cheer for Venus and Serena Williams. We all do it to some degree, be it with athletes or even “Price Is Right” contestants. We tend to support those representing our racial group.

It’s not racism. I prefer the term that movie producer (and soon to be Golden State Warriors owner) Peter Guber used repeatedly in his conversation with Charles Barkley in Barkley’s 2005 book “Who’s Afraid of a Large Black Man?”: tribalism.

Tribalism is about familiarity within the known entity. It’s not about hatred of others, it’s about comfort within your own, with a natural reluctance to expend the energy and time to break across the barriers and understand another group.

Most of what we’re quick to label racism isn’t really racism. Racism is premeditated, an organized class distinction based on believed superiority and inferiority of different races. That “ism” suffix makes racism a system, just like capitalism or socialism. Racism is used to justify exclusion and persecution based on skin color, things that rarely come into play in today’s NBA.

The league routinely gets A grades in Richard Lapchick’s racial report cards for diversity in its racial and gender hiring. While that doesn’t mean there’s complete equality in front offices and coaching sidelines, there’s no sense that a powerful invisible barrier bans African-Americans from those jobs like the sonic fence keeping out the smoke monster in “Lost.”

The color of LeBron’s skin won’t prevent him from making $14.5 million to play basketball for the Miami Heat this season. It didn’t prevent him from signing endorsement deals with corporate titans Coca-Cola, McDonald’s and Microsoft while in his early 20s. It didn’t keep people of all races from buying his jersey. Racism has yet to come into play in LeBron’s professional life. That doesn’t mean he can exist in a racial vacuum.

James managed to navigate the first seven years of his career without running into any racial reefs. You could say there was an African-American style to him, but he never presented any views as coming from a uniquely African-American perspective. All debates about LeBron were on his merits as a basketball player, as an individual, never linked to his ethnicity. There was a flare-up about the similarity of his Vogue magazine cover photo to a “King Kong” poster, but James didn’t join the discussion.

Lately there’s been a slow-moving racial weather front moving across the radar screen on the LeBron narrative, and ultimately he couldn’t escape the story.

It began with Jesse Jackson’s claim that Cleveland owner Dan Gilbert’s late-night rant about LeBron’s departure reflected a “slave master mentality” and that “He sees LeBron as a runaway slave.” It was an overly exaggerated reaction to the reaction. If Gilbert really saw LeBron as a slave, he would have tracked him down with bloodhounds and lynched him. That’s what slave masters did to escaped slaves. That’s why I’ll never equate professional or collegiate athletics to slavery.

Orlando Sentinel columnist Shannon Owens linked LeBron’s appearance on a list of 10 most disliked athletes to his race. And on ESPN.com, Vincent Thomas said the growing resentment toward LeBron from white people would increasingly lead black people to embrace him, almost reflexively.

Now James has entered the fray himself, simply by acknowledging the presence of something we’re never comfortable talking about. It came to his porch and he finally opened the door.

The counterargument is that James never felt compelled to address the league’s racial element when everybody was an ally. No one wondered about the racial motivations of reporters and fans when they were writing praise and buying jerseys.

That’s because race doesn’t affect acceptance, it affects tolerance. When people behave in a manner accepted by society at large they are easy for everyone to embrace. It’s who chooses to align with the outcasts that is telling.

LeBron quickly evaporated his reservoir of goodwill with the self-serving “Decision.” His own actions were responsible for the ignition and the acceleration of the vitriol. Where race comes in is the continuation. The racial element won’t be measured in the condemnation, which came from all corners. It will be measured in the willingness to forgive.

Self-indulgent? I always wondered why that tag didn’t stick with white athletes such as Eli Manning, John Elway, Danny Ferry and Kiki Vandeweghe, who refused to play for the teams that drafted them until they could force a trade. Did they avoid permanent ostracizing for their blatant attempt to circumvent the rules that are essential for competitive balance in the league simply because they were white? They certainly don’t pop up on the list when we talk about spoiled athletes.

LeBron, like the “draft dodgers,” never was accused of a major crime against society. But this week LeBron made a transgression that fewer are willing to forgive. He just forced us to discuss the existence of something none of us feels comfortable doing. He caused us to examine the bias that’s always lurking, that has the potential to spring from any of us. The color of LeBron’s skin won’t prevent him from making $14.5 million to play basketball for the Miami Heat this season. It didn’t prevent him from signing endorsement deals with corporate titans Coca-Cola, McDonald’s and Microsoft while in his early 20s. It didn’t keep people of all races from buying his jersey. Racism has yet to come into play in LeBron’s professional life. That doesn’t mean he can exist in a racial vacuum.

James managed to navigate the first seven years of his career without running into any racial reefs. You could say there was an African-American style to him, but he never presented any views as coming from a uniquely African-American perspective. All debates about LeBron were on his merits as a basketball player, as an individual, never linked to his ethnicity. There was a flare-up about the similarity of his Vogue magazine cover photo to a “King Kong” poster, but James didn’t join the discussion.

Lately there’s been a slow-moving racial weather front moving across the radar screen on the LeBron narrative, and ultimately he couldn’t escape the story.

It began with Jesse Jackson’s claim that Cleveland owner Dan Gilbert’s late-night rant about LeBron’s departure reflected a “slave master mentality” and that “He sees LeBron as a runaway slave.” It was an overly exaggerated reaction to the reaction. If Gilbert really saw LeBron as a slave, he would have tracked him down with bloodhounds and lynched him. That’s what slave masters did to escaped slaves. That’s why I’ll never equate professional or collegiate athletics to slavery.

Orlando Sentinel columnist Shannon Owens linked LeBron’s appearance on a list of 10 most disliked athletes to his race. And on ESPN.com, Vincent Thomas said the growing resentment toward LeBron from white people would increasingly lead black people to embrace him, almost reflexively.

Now James has entered the fray himself, simply by acknowledging the presence of something we’re never comfortable talking about. It came to his porch and he finally opened the door.

The counterargument is that James never felt compelled to address the league’s racial element when everybody was an ally. No one wondered about the racial motivations of reporters and fans when they were writing praise and buying jerseys.

That’s because race doesn’t affect acceptance, it affects tolerance. When people behave in a manner accepted by society at large they are easy for everyone to embrace. It’s who chooses to align with the outcasts that is telling.

LeBron quickly evaporated his reservoir of goodwill with the self-serving “Decision.” His own actions were responsible for the ignition and the acceleration of the vitriol. Where race comes in is the continuation. The racial element won’t be measured in the condemnation, which came from all corners. It will be measured in the willingness to forgive.

Self-indulgent? I always wondered why that tag didn’t stick with white athletes such as Eli Manning, John Elway, Danny Ferry and Kiki Vandeweghe, who refused to play for the teams that drafted them until they could force a trade. Did they avoid permanent ostracizing for their blatant attempt to circumvent the rules that are essential for competitive balance in the league simply because they were white? They certainly don’t pop up on the list when we talk about spoiled athletes.

LeBron, like the “draft dodgers,” never was accused of a major crime against society. But this week LeBron made a transgression that fewer are willing to forgive. He just forced us to discuss the existence of something none of us feels comfortable doing. He caused us to examine the bias that’s always lurking, that has the potential to spring from any of us.

Written By J.A. Adande

Leave a Reply