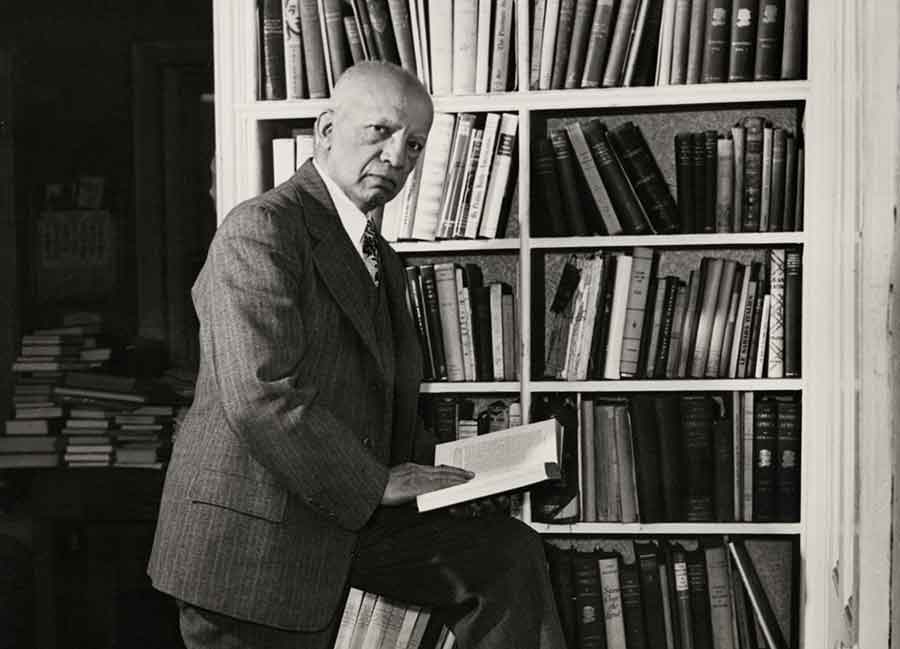

(ThyBlackMan.com) Langston Hughes has always held a special place in my heart—not just as a literary icon, but as a voice that’s guided me through different chapters of life. His words are like old friends: familiar, comforting, sometimes challenging, but always honest. Most people know him through his famous works—the ones we all read in school or hear during Black History Month. But what about the poems that don’t get as much love? The ones tucked away in collections, the ones that whisper instead of shout?

This month, as we honor National Poetry Month, I wanted to shine a light on some of those lesser-known poems. They may not be the ones quoted at rallies or printed on posters, but they hit just as hard—sometimes harder. These are the poems where Hughes gets intimate, political, satirical, or deeply reflective. They show different shades of who he was as a poet, a thinker, and a human being.

I hope this list introduces you to a new favorite—or helps you see a familiar poem in a new way. More importantly, I hope it reminds you that even the quietest verses can carry the loudest truths.

1. “God to Hungry Child”

This brief but striking poem exemplifies Langston Hughes’ ability to blend the sacred with the socially urgent. In “God to Hungry Child,” Hughes does not merely criticize abstract spirituality; he interrogates the institutions and ideologies that offer faith in place of food. The speaker is a child—a figure of innocence and vulnerability—asking why spiritual promises do not satisfy physical hunger. This poem becomes an indictment not just of God as a symbol, but of those who claim to serve divine purpose while allowing suffering to persist.

The structure is sparse, its economy of language purposeful. Hughes leverages brevity to emphasize the stark contrast between theological platitudes and lived reality. This is a poem where tone is everything—where disappointment simmers into disillusionment. The child’s voice is not angry in the traditional sense; it is exhausted. That exhaustion becomes a powerful emotional current, revealing the limits of spiritual comfort in the face of real-world deprivation.

Furthermore, for lovers of poetry, the poem’s strength lies in how Hughes uses understatement. He doesn’t need to lecture; instead, he allows the image of a hungry child questioning a distant God to speak volumes. The tension between religious symbolism and existential hunger is an age-old concern, yet Hughes handles it in a way that is thoroughly modern and deeply human.

This poem is especially relevant today as debates around poverty, social welfare, and the role of religious institutions continue. Hughes encourages the reader not only to reflect, but to act—reminding us that poetic expression can be a moral awakening.

2. “Johannesburg Mines”

“Johannesburg Mines” transports the reader beyond American soil, offering a glimpse into the brutal labor conditions endured by Black South African workers under apartheid. Hughes is clear-eyed in his internationalism, recognizing that the exploitation of Black bodies and labor is a global phenomenon. What’s remarkable is how seamlessly he draws a parallel between economic structures in South Africa and those in the United States, showing that the machinery of racialized capitalism knows no borders.

In terms of form, the poem is deceptively simple, but each line functions like a chisel against the stone of injustice. Hughes sketches the lives of miners with stark imagery: tired bodies, relentless work, and forgotten lives buried beneath the weight of profit. These are not just workers—they are symbols of global inequality. And Hughes’ tone is not just empathetic; it is defiant. He speaks to a collective Black consciousness that resists silence and invisibility.

For readers with a keen interest in postcolonial literature, “Johannesburg Mines” is a profound entry point into understanding Hughes’ solidarity with liberation movements outside of the U.S. The poem also raises questions about the complicity of global markets in human suffering—a discussion that feels eerily contemporary in our age of global capitalism.

Poetry lovers will appreciate how Hughes compresses history, politics, and emotion into a tightly focused lens. His global sensibility sets him apart from many of his contemporaries and proves that poetry can function not only as art but as international witness.

3. “Advertisement for the Waldorf-Astoria”

A brilliant piece of poetic satire, “Advertisement for the Waldorf-Astoria” remains one of Langston Hughes’ most radical social commentaries. Written during the height of the Great Depression, it critiques American consumer culture and economic disparity by presenting a mock advertisement for one of the most luxurious hotels in New York City. What makes this poem so biting is that Hughes appropriates the very language of luxury marketing to illuminate the absurdity of promoting opulence when millions were suffering in breadlines.

This is Hughes at his most experimental. Structurally, the poem mimics a print ad, complete with section headers and prices, blurring the boundary between journalism, poetry, and polemic. By juxtaposing rich language about champagne dinners and plush bedding with the stark poverty faced by Harlem residents, Hughes crafts an ironic masterpiece that forces the reader to confront uncomfortable truths.

The poem’s audience is intentionally ambiguous. Is it directed at the elite who live lavishly while ignoring the poor? Or at the masses who are conditioned to aspire toward unattainable wealth? Either way, Hughes uses the poem as a tool of disruption—undermining capitalist fantasy by injecting it with poetic realism.

Literary scholars and poetry aficionados alike should study this poem not only for its content but for its daring structure and tone. Hughes breaks conventional poetic form to deliver a more urgent kind of art—a reminder that poetry can wear many masks, including that of the very system it seeks to dismantle.

In today’s world of increasing income inequality, “Advertisement for the Waldorf-Astoria” remains shockingly relevant. It challenges readers to consider how far we’ve truly come—and how often poetry must bear the burden of truth-telling when the media fails.

4. “Ballad of the Landlord”

This powerful narrative poem is one of Hughes’ most underappreciated works when it comes to dramatizing everyday injustice. “Ballad of the Landlord” begins with what appears to be a tenant’s casual complaint—broken stairs, a leaky roof—but quickly escalates into a confrontation that results in the tenant’s arrest. In just a few stanzas, Hughes exposes the systemic racism embedded in housing, law enforcement, and the media.

The poem’s structure is conversational and rhythmic, drawing on the ballad tradition to make it both accessible and emotionally resonant. Yet beneath its musicality lies a deep critique of power and perception. The landlord dismisses the tenant’s concerns, the police overreact, and the newspaper distorts the story—all familiar themes in marginalized communities, then and now.

What is particularly genius here is how Hughes plays with voice. The speaker’s tone shifts from reasoned complaint to exasperated threat, and it is at that moment that the system clamps down. This mirrors the real-world phenomenon of Black anger being criminalized while white negligence goes unpunished.

For lovers of poetic storytelling, this piece is an extraordinary blend of narrative, dialogue, and activism. It reads like a short story condensed into verse, proving that poetry can carry the same emotional and thematic weight as fiction, if not more.

Moreover, it is an important work to examine through the lens of racial justice, particularly in contemporary discussions about housing discrimination, police brutality, and media bias. The issues Hughes raised in this poem remain alarmingly present today.

“Ballad of the Landlord” is also a testament to Hughes’ skill in bringing social realism into the poetic realm without sacrificing form or musicality. It is the kind of poem that opens classroom discussions, sparks debate, and, most importantly, refuses to be forgotten.

5. “Kids Who Die”

“Kids Who Die” stands among Langston Hughes’ most emotionally potent and politically courageous poems, yet its place in popular literary discourse remains surprisingly muted. The poem does not eulogize in the traditional sense—it demands that the reader remember the unnamed children who are too often sacrificed on the altar of oppression. These children are not granted statues or textbooks; they are erased from the mainstream narrative, their lives considered expendable, their deaths rendered invisible.

Hughes refuses to allow these lives to be lost without acknowledgment. His voice in the poem is bold, direct, and unrelenting. There is no poetic sugarcoating; instead, there is a drumbeat of righteous indignation. By focusing on children—symbols of innocence, potential, and future—Hughes intensifies the moral outrage. These are not abstract victims; they are young people gunned down by systemic neglect, racism, and state violence. Hughes insists that they will one day be recognized as foundational to future freedom movements.

The poem operates on multiple registers: it is part elegy, part prophecy, and part revolutionary manifesto. Hughes names the ways these children are killed—not only by violence, but by poverty, neglect, and silence. For scholars and lovers of poetry, this work is a brilliant example of how the poet leverages voice and tone to transform grief into defiance.

It is also crucial to read “Kids Who Die” in the context of our current moment, where many young people—especially young Black and Brown individuals—still fall victim to gun violence, police brutality, and structural inequalities. Hughes was not just writing about his own era; he was writing into ours.

This poem should be at the forefront of any serious study of political poetry and should be revisited not just during commemorative months, but as a guiding text for conscience and cultural memory.

6. “Border Line”

Whereas many of Hughes’ political poems are defined by external action or social critique, “Border Line” turns the lens inward. It is a poem about interior space, about the emotional cost of being constantly othered and displaced. The border, in this case, is not merely geographic—it is existential. The speaker exists in a liminal space, not fully welcomed, not fully rejected, perpetually in-between.

There is a mournful restraint in the language, a quiet ache that feels almost confessional. Hughes uses ambiguity to great effect; we are never told exactly what the speaker has endured, but we feel it in every syllable. This economy of language is a testament to Hughes’ ability to do more with less. The emotional gravity of the poem lingers, like a haunting afterimage.

“Border Line” is also notable for its thematic complexity. It touches on identity, alienation, and longing, making it fertile ground for readers interested in intersectionality and the psychological effects of systemic marginalization. The poem doesn’t present answers—it dwells in the uncertainty, the loneliness of being neither here nor there.

For poetry lovers who value introspective writing, this poem is an invitation to reflect on belonging, citizenship, and emotional exile. It resonates with those who have felt dislocated by race, class, gender, or sexuality. Hughes, who was himself often between worlds—Black and white, North and South, rich and poor—imbues this piece with autobiographical resonance that transcends the personal.

This poem deserves a place alongside Hughes’ most famous works because it shows a different side of his genius: one that whispers instead of shouts, that aches rather than protests, and that mourns without ever relinquishing truth.

7. “Let America Be America Again”

“Let America Be America Again” may be more recognized in contemporary political speeches and protest placards, but it still does not receive the in-depth literary attention it deserves. This is a sweeping, ambitious poem that operates on multiple levels—political, philosophical, and poetic. Hughes dares to confront America’s self-congratulatory mythology and contrasts it with the lived experiences of those who have been excluded from its promises.

The poem’s structure is dynamic, shifting perspectives between an idealistic narrator and the disillusioned voices of those denied access to liberty and equality. This chorus of the unheard—Black Americans, Native Americans, immigrants, and the working class—transforms the poem into a symphony of resistance. Hughes becomes a literary conductor, weaving together the pain, betrayal, and hope of America’s marginalized.

What makes the poem particularly effective is that it is not purely accusatory. Rather, it is profoundly aspirational. Hughes does not reject America outright; he demands that it live up to its own ideals. In this way, the poem walks a tightrope between critique and hope. It’s a love letter written in frustration, a patriotic hymn laced with bitterness and longing.

Thematically, this poem is relevant not just for Black Americans but for anyone whose version of the American Dream has turned into disillusionment. It has been used in political campaigns, social justice movements, and classrooms, but rarely is its full poetic power explored.

For poetry readers and scholars, this is a piece that rewards multiple readings. It is rich in rhetorical devices—anaphora, juxtaposition, tone shifts—and stands as one of the best examples of how poetry can articulate collective consciousness. During a time when debates around nationalism, immigration, and inequality dominate public discourse, this poem serves as a moral compass.

“Let America Be America Again” is not simply a poem—it is a national reckoning. It should be canonized alongside the country’s most revered founding texts for its unflinching honesty and unyielding hope.

8. “Troubled Woman”

“Troubled Woman” may be one of Langston Hughes’ shortest and quietest poems, but it stands as a masterclass in minimalist storytelling and emotional depth. The poem doesn’t name its subject directly, nor does it provide a linear narrative, yet it conjures an image of a woman whose life has been shaped by enduring sorrow and persistent survival.

There is something sacred in Hughes’ portrayal—an unspoken reverence for the strength required to endure trauma. The woman in the poem is not pitied; she is recognized. That recognition becomes an act of poetic justice, a way of honoring the lives often dismissed by history and literature.

Hughes doesn’t romanticize the woman’s pain, nor does he exploit it. He simply presents it—raw, distilled, and deeply human. In doing so, he makes a powerful statement: even the quietest lives deserve to be witnessed. This aligns with one of Hughes’ enduring literary missions—to give voice to the voiceless and dignity to the disregarded.

For readers who appreciate poetry that captures emotional landscapes rather than explicit events, this piece is incredibly effective. It invites introspection, encouraging the reader to fill in the blanks with their own understanding of what “trouble” might mean in a racialized, gendered society.

Academically, “Troubled Woman” can be analyzed through multiple lenses—feminist, psychoanalytic, or even theological. Its brevity makes it accessible, but its emotional weight makes it enduring. Hughes shows us that sometimes the most profound stories are the ones that barely speak above a whisper.

In a world that continues to overlook Black women’s stories, this poem remains a poignant tribute to silent strength. It reminds us that poetry is not just about volume or complexity—it is about truth, no matter how quietly it is told.

When I revisit these poems, I’m always struck by how ahead of his time Langston Hughes really was. He didn’t just write poetry—he documented struggle, joy, rage, and resilience. He held up a mirror to America, and in doing so, offered a kind of spiritual and cultural roadmap for generations to come.

These eight lesser-known poems remind me why I fell in love with his work in the first place. They may not be the headliners, but they carry depth, fire, and soul. If you’ve never read them before, I hope you sit with them—really sit with them. And if you have? Revisit them. They tend to speak differently depending on where you are in life.

And now, I want to hear from you: What’s your favorite Langston Hughes poem? Maybe it’s one you grew up with. Maybe it’s one you stumbled across in a moment of need. Either way, I’d love to know why it matters to you.

Because that’s the beautiful thing about poetry—it connects us, across time and space, through feeling.

Staff Writer; Jamar Jackson

Leave a Reply