(ThyBlackMan.com) You know it’s coming. Of course it is.

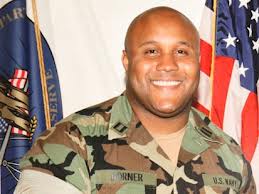

Even as you read this, somewhere in Hollywood an anxious, enterprising producer is having a Christopher Dorner script developed.

Names like L.L. Cool J and Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson are being bandied about. Or producers could simply recruit an unknown with an engaging smile and 20-inch biceps.

In any case, the tale of Christopher Dorner, 33, the former Los Angeles Police officer charged with shooting attacks on police officers and their families from February 3 to 12 that left two civilians and two police officers dead and three officers wounded, is certainly the stuff of movies.

His story has it all—drama, the little-man-vs.-the-machine, guns, action, extreme violence, intrigue, guns, irony, more guns, enough heartbreak to go around and controversy that cuts down racial political and socio-economic lines.

However, unlike most biographical films, with Christopher Dorner’s story, you wouldn’t have to embellish much. The truth is engaging on its own.

You hope whoever makes the flick, gets it right. For instance, the film would have to establish early on who Christopher Dorner apparently was: an often fanatical do-gooder whose fragile, almost naive psyche didn’t leave much room for the idea that the world isn’t always fair.

room for the idea that the world isn’t always fair.

It’s safe to assume Christopher Dorner’s mother raised her son to know the difference between right and wrong. Accordingly, when what is encouraged in a child is deemed correct by both parent and society, not many people can tell that child otherwise. Thus, as Christopher Dorner wrote in his infamous manifesto, when a white grade school classmate called him nigger, he felt perfectly justified in physically retaliating.

However, a school official reprimanding both the kid for using the racial slur AND Dorner for getting physical, was no doubt seminal in shaping must have been a recurring theme in Dorner’s mind: I’m always picked on, singled out–PERSECUTED–for doing the right thing.

That experience wouldn’t stop Christopher Dorner from choosing right over wrong. During his Navy enlistment, while in Enid, Oklahoma Dorner found a bag containing $8,000. Police were curious as to why a young man would turn in that kind of dough (it belonged to a church) instead of simply keeping it for himself. Dorner reportedly responded that his mother taught him “honesty and integrity.”

Christopher Dorner’s sense of honor wasn’t always appreciated at the LAPD, which he joined in 2005. When he reported to supervisors witnessing his training officer kick a mentally ill man while he was handcuffed and lying on the ground, the charge led to an internal review board.

The board ruled that Dorner falsified the report to counter claims by his training officer. Dorner’s performance in the field needed improvement, wrote the officer.

Christopher Dorner’s firing–and subsequent series of court rulings and appeals during which he unsuccessfully sought to “clear my name”—are what lit the fuse of combustible pride, ego and emotional instability. Dorner snapped.

A responsible movie about Christopher Dorner would include a Technicolor glimpse inside the LAPD, where, according to Dorner and working and retired officers, the efforts of honest officers are sullied by police who abuse their power with both citizens and fellow officers. Despite the “inclusion” of women and officers of color, law enforcement

It’s not the job of filmmakers to make Dorner a hero or a villain. The mission is to simply tell the story of a man who’d had enough, completely lost his mind and launched a campaign of revenge. He murdered a young, engaged couple as they sat in a car one night, she being the daughter of a former LAPD captain who had defended Dorner at a disciplinary hearing. Dorner didn’t think he worked hard enough on his behalf.

During the nine day manhunt, police committed some of the very illegalities Dorner’s manifesto said officers do everyday: after the manhunt, LAPD bought a new truck for two women wounded when police riddled their vehicle with bullets as they delivered newspapers in the wee hours of the morning. The truck didn’t fit the description of Dorner’s.

In a movie that told the truth, the media covering the Dorner case wouldn’t look good. Inept and judgmental, both L.A. and national media often reported the news as it saw fit, omitting important details, speculating on-air and occasionally getting the information flat-out wrong.

Christopher Dorner’s on-screen tale wouldn’t be complete if it didn’t communicate the pain of the families of those who were killed, all of whom are victims as well. That last officer killed comes to mind. He didn’t have to participate in the search that day, but chose to.

I try to imagine the immense grief of Dorner’s mother, whose joy of seeing her son become a peace officer evaporated when her flesh and blood–her baby–became target of the largest manhunt in the history of California.

Finally, I think of Dorner himself, a mystifying, proud and troubled dichotomy of a man who willfully and with sinister, methodical premeditation plotted a one man war against one of the largest, most well-equipped police forces in the world.

Here was a man who had absolutely lost it–—but who apparently maintained remarkable presence of mind.

During their press conferences, continually LAPD characterized Dorner as an extreme danger to all, but had he gone on an indiscriminate shooting spree, more people would have killed.

Indeed, Dorner was a man of contrasts: crazed and in a take-no-prisoners mode, he was kind and calm to the middle aged couple he tied up when they walked in on him in their cabin. He promised not to kill them. “I didn’t want him to die,” the wife told reporters.

Apparently, there wasn’t a woman in the picture–Dorner was divorced. Trust Hollywood to take care of that.

The facts are that he was hunted by the LAPD. And Sheriff’s departments. And the FBI. They had helicopters. Armored vehicles. Infrared capability to see in the dark, and a million dollar bounty on his head. And they couldn’t find him. If his truck hadn’t broken down early days of his flight, he still might be out there. He died in a cabin that went up in a fire that may have been deliberately set by officers. This is a movie.

Truth is, any film about Christopher Dorner worth watching would be about more than just Dorner and what does or doesn’t go on inside LAPD. It would also be about the systematic, generational ignorance and hate that has always America in its grip.

We are a modern, forward thinking society–and we still deal with ancient, fear-fueled bigotry. Still.

If a film about Christopher Dorner dared make the connection between his personal madness and our crippling national psychosis, then perhaps in the hearts and minds of at least those sitting in the theatre, “The End” might signify a beginning.

Written By Steven Ivory

….just another killer. So the tear gas ignited? Tough stuff. He had just killed one officer and wounded another. Burn his ass out or fry him. Works for me.

Did the police set the fire? Follow link below.

http://www.fox19.com/story/21202930/did-authorities-set-fire-to-the-cabin-where-ex-cop-was-hiding

Dorner domain names already being bought up.

http://DornerManifestoMovie.com

http://dornermanifesto.com

http://dornermovie.com

http://DornerThemovie.com

Capitalism at its best!

Being on the job market as a Black individual is like being in a Godfather movie without any protection!!!

I agree that the story needs to be told. I didn’t know the report of Dorner was falsified and I am sure there are plenty of other things we ignore. This goes way beyond Dorner, we have been through hell for too long on the job market, etc. Things didn’t change that much. I finished yesterday to watch Blood Done Sign my name based on a true story. It was very interesting to see that all the men who were persecuted by the police were Black when the viewers saw the pictures Wanted at the police station. I thought right away about Dorner. In addition, we learn that the first Black policeman in the small town of North Carolina was not allowed in four years to arrest a White man. They really respect our authority, lol!!!

To the poster above, you state that violence committed by blacks is always explained? That’s not true, quite the opposite infact most white killers are usually deemed as “mentally disturbed” think Adam Lanza and James Holmes, those are just two examples of white men who were certified as mentally ill. Blacks on the other hand are seemingly depicted as cold blooded murders or plain evil.

He’s no hero, he was a mass murderer, and I strongly doubt that if he were a white man there would be any talk of making a movie. Violence by blacks seems to be excused or explained away in American society, while everybody apparently agrees to pretend the opposite is taking place. Why?