(ThyBlackMan.com) A gangsta-inspired double-consciousness?

I think I’m Big Meech/Larry Hoover?

Whipping work/hallelujah?

One nation/under god ?

Real n*ggas getting money from the fu*king start?

–B.M.F (Blowin Money Fast) by Rick Ross featuring Styles P??

Earlier this month, Casey Gane-McCalla, a journalist, rapper, comedian and Facebook friend, declared on his FB status: “I am an Ivy league college educated journalist with no criminal background…still when I hear this song…I think I’m Big Meech.”

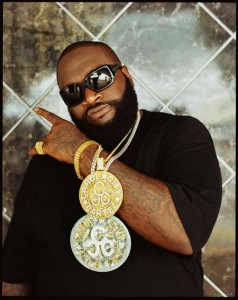

The song that Gane-McCalla refers to is B.M.F, a single from Rick Ross’s fourth album, Teflon Don which dropped Tuesday. The song’s considered a heater. The summer’s hip-hop anthem.

His admission came as I started to notice more and more black male friends and associates like Gane-McCalla embrace Rick Ross with fingers thrown in the air. These are: college graduates who own all of the rapper’s albums,  recite his lyrics passionately, and wear dress shirts and ties to work daily even though it’s not required. These are: corporate ladder-climbers who admit that Ross is growing on them and wonder why I don’t agree. These are: straight-laced brothers who turn up the radio and head nod hard to gangster stories attached to thumping beats. These are: Ivy-leaguers who, even just for the length of the song, feel like they’re Big Meech.??

recite his lyrics passionately, and wear dress shirts and ties to work daily even though it’s not required. These are: corporate ladder-climbers who admit that Ross is growing on them and wonder why I don’t agree. These are: straight-laced brothers who turn up the radio and head nod hard to gangster stories attached to thumping beats. These are: Ivy-leaguers who, even just for the length of the song, feel like they’re Big Meech.??

Read a critique of how the hip-hop industry thrives on our demise.

Some context: Demetrius “Big Meech” Flenory, cofounded the notorious, drug cartel BMF (Black Mafia Family). It’s been estimated that the organization, led by he and his brother Terry “Southwest T” Flenory, pulled in more than $250 million during its reign.??

Big Meech lived the lifestyle so many rappers claim and celebrate. Cases of champagne at the club. Host of luxury cars. He beamed money-green and really did blow money fast. Women swooned and brothers bowed. His crew was air-tight; zero tolerance for disrespect.

The hypermasculine dream. Until the inevitable fall in 2008, when Big Meech received a thirty-year prison sentence for running a criminal enterprise.

So why would black men, who possess the legitimized American dream credentials: good education, better job, nicer salary, property in their own name, sometimes feel, as Ross has termed, “meechy”?

“I think that many professional and educated black men feel constrained in their day-to-day realities,” says Mark Anthony Neal, professor of African & African-American Studies at Duke University. ??

“Particularly,” he adds, “in relation to their performances of masculinity, where they are always conscious of how their ambition, aggression and physical presence is interpreted by white colleagues and superiors. Call it the Obama syndrome.”

Enter Rick Ross. A dream’s vessel. A movie director, shaping and crafting imagery using a repetitive script.

In B.M.F, the crime-laden dialogue and cues are laid with ferocity over a nastier beat: being self-made, versus being affiliated; building from the ground up, no renovating; penetrating claimed women.

The middle-finger American dream—one that multiple-degreed brothers can pump fists to at the club, groove to on the way to work, or listen to on their iPod at the gym. Unharmed.

“Unlike the many little kids in the ghetto who will fight to be the next Big Meech, I have no plans in following in his footsteps,” admits Gane-McCalla. “Still, I sing along with Rick Ross’s song. Why? Is it my Michael Corleone Godfather Soprano fantasy? Probably. A rap song can temporarily lift me from my safe, yet hardly lucrative position of a journalist to the fast exciting world of being a drug dealer. A world I can quickly exit without fear of getting shot or incarcerated.”??

Life as code-switching? A gangsta-inspired double-consciousness? ??

“Big Meech allows some of these men to perform an alternative version of themselves,” says Neal, “and what is critical, is that they fully understand that it’s an alternative performance that must be managed away from their professional lives.”??

The radio gets turned down as they approach the office. And often, the next performance begins in the workplace to appease white colleagues. ??

“Rick Ross becomes an ideal symbol of [alternative performance],” Neal notes, “because given the questions about his back story, most folk are clear that he is all performance, but one that remains compelling and attractive.”

Ross’s credibility was marred back in ’08 when allegations emerged that he had worked as a correctional officer. Surprisingly, his rapper card wasn’t revoked. He bounced back through denial and a tighter hold to I’m real convictions. A politician in the making.??

However, not all black males have the luxury to drift in and out of the Big Meech fantasy. “Still for the millions of little black children who see being the next Big Meech as they’re only outlet for success,” Gane-McCalla says, “that world is not as easy to exit.”??

This isn’t to suggest that Ross is the first image peddler or the last. Nor is it to suggest this is the first complicated relationship between fantasy maker and outside spectator. There’s the overused hip-hop paradigm of the suburban white kids who consume gangster culture on demand, without investment in its sociopolitical implications. The difference here is that even as these professional men move further away from the black man as a thug image, that divide could be instantly closed by media, police officers, or employers who rely on stereotypes to navigate the world and retain power.

Let Ross tell it though, the connection is about a shared desire for achieving. “It’s just about being creative, being flyer than you were yesterday,” he told AllHipHop.com about his success. “I wake up and try to do that. You got to switch the color of the stones up sometimes, go to new heights, you got to go above and beyond the lames…it makes for great television.” ??

And according to him, B.M.F isn’t just about celebrating thirty-year prison sentences. It’s “getting out of the recession” and “back on the grind” music. The song is about “the struggle,” Ross explained in a recent interview with DC’s WKYS 93.9. ??

These days struggle is relative. Some brothers war with injustice. Some battle poverty. Others fight corporate bullying as they try to secure a dream that wasn’t originally designed with them in mind. Yet most must combat the stereotypes that media, racist institutions, their brothers, and perhaps they themselves perpetuate.

?Struggle has always needed a soundtrack and for some black men, it may just be the music—catchy rhymes and hot beats—that attracts them. “Despite the glorification of crime, B.M.F is a dope song,” Gane-McCalla admits.??

But he’s sure to add that he can’t stop thinking how much better it would be if the hook was:??

“I think I’m Malcolm X/Martin Luther?

I seen the mountain/hallelujah

One nation/under god ?

Real brothers make change it’s the fu*king squad”

Written By Felicia Pride

swag it out! haha nah this is pretty cool though