(ThyBlackMan.com) Dead uncle in the middle of the road. Do you hit the brakes or accelerate? Depends on…

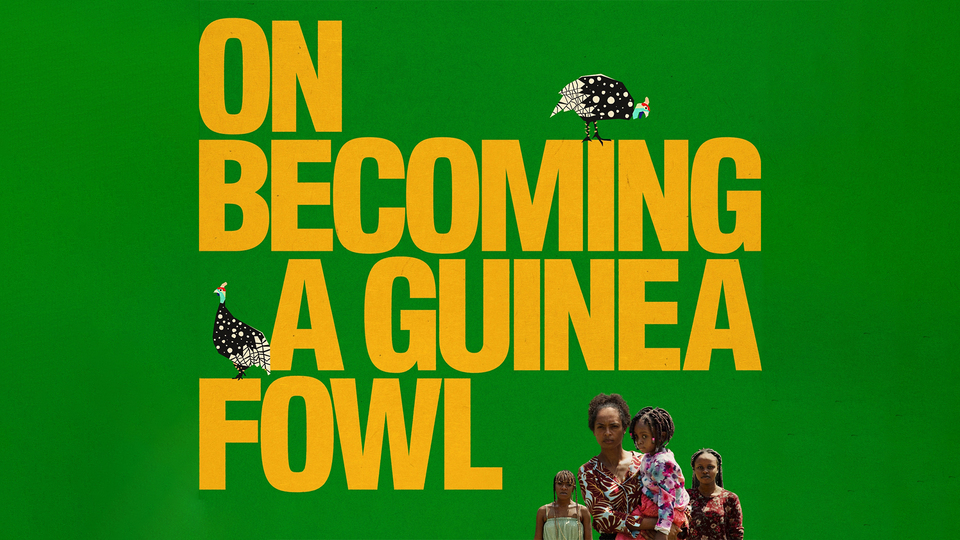

British writer/director Rungano Nyoni has her own take on the #MeToo movement as it concerns her home country, Zambia. She prefers a modern fable. One in which the protagonist must find her voice to speak the truths about what has happened.

The model for the behavior she must conjure to set things right is not a human. It’s a guinea fowl. As explained in an educational program kids are watching on a TV in the movie, the African bird is often used as a watch dog on farms and has a purpose: “Guinea fowls are very useful. When they see a predator, they make a noise. It says, ‘look out there’s danger about!’” And so, it goes.

One night Shula (Susan Chardy), a twentysomething is out driving around Zambia, headed home from a party. A mirrored mask with imbedded sunglasses is her headwear, a black balloon-type costume is her garb. She sees something in the road. Stops her car. Under closer scrutiny she recognizes the body. It’s her Uncle Fred (Roy Chisha), her mom’s (Doris Naulapwa) brother. She sits in her car in shock. Calls her dad (Henry B.J. Phiri), who, as usual, isn’t much help: “Stay there in the car. I’m coming. But send me money for a taxi.”

Oddly Shula’s crazed cousin Nsansa (Elizabeth Chisela) is nearby and almost taunting Shula as she maneuvers herself into the vehicle. Over the next hours and days, folks will gather at Shula’s mom’s house to show respect for Uncle Fred, grieve and divide up his assets. Families from his side and his very young wife’s side will meet and hash things out. Meanwhile, the female cousins talk, and the old women conceal. Fred “messed” with a lot of girls. He’s gone, but surely his place in the afterworld is hot and fiery and not so heavenly.

Those expecting this allegory to be told in a Western way should be patient and ready to experience how a culture from The Mother Continent handles a universal social issue. Opening scenes with Shula in her car, distressed and remembering a man who left a bad mark on her, are exceedingly slow. To the point of stymying the storyline and waylaying interests. But stick with it.

As Fred’s sordid past is revealed, women who were abused as girls and caught in his web speak out. As they do, the narrative gets heavier, and the odd humor vanishes. Things get serious and more thoughtful by the minute. Like Nyoni is building her case against the deceased and his kind of behavior. She does so like a griot. Much like the world-renown Mauritanian director Abderrahmane Sissako did with his fables, like Timbuktu.

The women talk. They need to. Some have been supportive in their sisterhood. Others have swept things under the rug. But a new day is coming. Something is brewing. Behavior once tolerated may be called out. Those who were complicit will be held accountable. Maybe not in a call-the-sheriff- kind of way. But accountable, nonetheless.

Shula, as played well by Chardy, isn’t the perfect emissary. But she’s the chosen one. Remembrances of abuses past are fresh in her mind. Young cousins like Bupe (Esther Singini) manifest their haunting memories in their own way. Shula is able to commiserate with and support them. That’s empowering. Doesn’t matter how you get to the day of reckoning, just that you get there.

The cinematography is fine but doesn’t stand out the way it did with Nyoni’s 2018 BAFTA Award-winning I am Not A Witch, which was also shot by David Gallego. When the footage isn’t focused on shiny masks or the red dresses the matriarchs wear, the everyday clothes by costume designer Estelle Don Banda and ordinary production design by Malin Lindholm seem fitting, natural and blend in.

Lucrecia Dalt’s score makes sense, and the playlist brings hints of modern Afrobeat music with infectious tunes like “Godly” by Omah Lay. Editor Nathan Nugent needed a more concise approach to his cuts in the first scenes, which dragged momentum when the film needed it most. After the 20-minute mark, the footage’s rhythm finds its beat, which last for the rest of the 99-minute running time.

There are many reasons why those who’ve been sexually abused don’t speak up. E.g., undeserved shame. But another roadblock that hinders healing, talking and change is not wanting to make waves. As Shula struggles for clarity about her experiences, she assesses what blocked her from moving forward: “All those years everything going on with me. I didn’t tell my family, cause I didn’t want them to break.”

The second and third act of the narrative get stronger. The heaving of guilt off the victim and onto the perpetrator and abettors will resonate with audiences long after the final credits roll. They’ll forgive the lack of inertia in the beginning. Ditto the ending, which doesn’t go far enough. They’ll discover how Zambians gather upon the death of a loved one and what they do. Says one snarly patriarch to the grieving much younger widow (Norah Mwansa), who’s been left behind by her lecherous husband Fred: “The widow is crying like a mosquito!” That derision is unwarranted. It merits a confrontation.

The movie hits its main point after that moment. When you think Fred has left this earth with his good reputation in tack and his victims on the defensive. That’s when someone must decide to hit the brakes or accelerate.

Trailer:

Written by Dwight Brown

Leave a Reply