(ThyBlackMan.com) Everyone loves a good story. Whether told by spoken word or shared in the pages of a book, there’s nothing quite like following the ups and downs, the unexpected plot twists, the emotional roller coaster offered by a good story. Of course, we were taught in our younger years, probably during elementary school, that there are generally two kinds of stories: fiction or nonfiction. Anything, it seems, is allowed in fiction. And that’s why people love it. Fictional stories are filled with dragons and wizards, ghosts and monsters; and, sometimes, they depict human beings—just like you and me—but who have superhuman abilities like, say, to go superfast (like The Flash) or, when angered, can transform into a super-strong creature (like The Hulk). Nonfiction, on the other hand, does not offer these flights into fantasy, at least it isn’t supposed to. It’s about facts. It’s about what really happened. And it is believed (or hoped) that the most transparent stories told in the nonfiction genre are autobiographies. In essence, this mode of storytelling gives someone the freedom to tell his or her own story in their own words. But what makes a good autobiography?

Oftentimes, we find ourselves drawn to a person’s story for the same reasons we are drawn to fictional tales. There is something unreal about this person’s life. When reading the esteemed autobiographies, we find ourselves asking, “how did he do all of that?” or “did she really survive that tragedy?” or “how did they keep that a secret for all this time?” For one reason or another, there is an element of the superhuman in these real stories. The slave narratives, such as Frederick Douglass’s My Bondage and My Freedom, document the real superhuman acts of men and women who risked all to achieve their physical, psychological, and spiritual freedom. And then there are the stories telling of real self-discovery. Here we learn of the wayward soul, perhaps born on the wrong side of the down, perhaps destitute and forlorn, perhaps abandoned by family and friends, perhaps rejected from society, who is lost. In these stories we find a person who hasn’t just hit rock bottom but, it seems, has lived their entire life at rock bottom (or, in extreme cases, at the bottom under a rock).

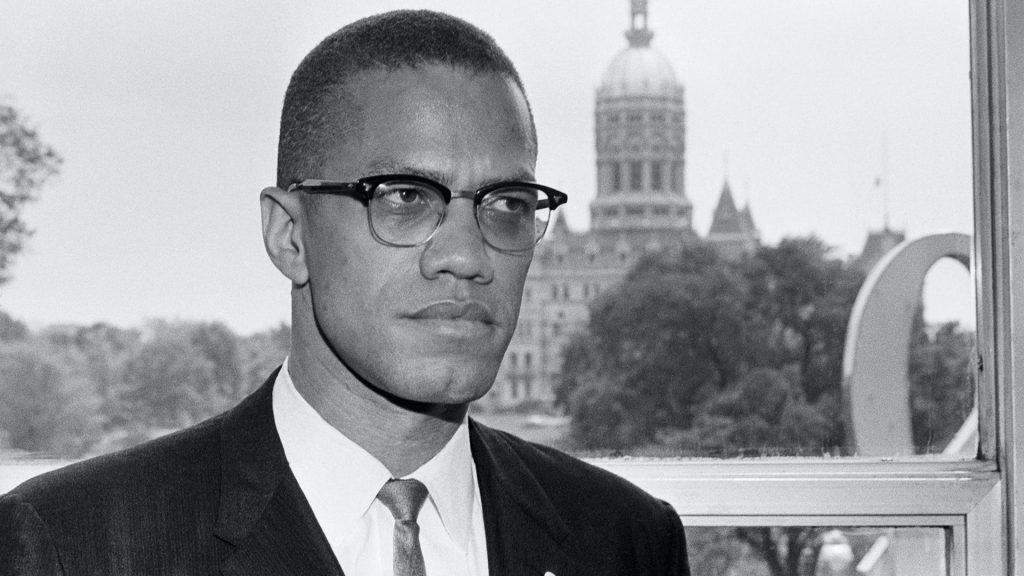

But isn’t this what makes the great autobiographies truly great? Overcoming tremendous obstacles, real-life trials and tribulations, make these stories real to the reader. And, when it’s really real, we see ourselves in the story. It can be argued that this is the central reason why, for many readers, especially throughout the African diaspora, The Autobiography of Malcolm X: As Told to Alex Haley is one of the greatest autobiographies of all-time. Originally published in 1964, the book remains a best-seller; in fact, according to Amazon’s best seller rankings the book, today, is #2 in books about Islam, #3 in religious leaders’ biographies, and #5 in political leaders’ biographies. People, the world over, are still captivated by Malcolm X’s story.

I have spoken with several people who tell me, sometimes with tears in their eyes, that The Autobiography of Malcolm X changed their lives. A handful of these persons, for one, focus on Malcolm’s militancy, the fact that he spoke his mind, unapologetically. Of course, an example of Malcolm’s untamed rhetoric is the now infamous “the chickens coming home to roost” comment that he made after the assassination of John F. Kennedy. That is not the only time Malcolm spoke his mind, however. In a 1965 interview with the “New York Times” Malcolm shed light on his break with the Nation of Islam, stating that, though at one time he devoted his mind, soul, and voice to the organization and its leader, he was now thinking and saying things for himself. As he matured, he became more convinced that he was not going to let anything or anyone control his mind—or his mouth. There are others, though, that focus on Malcolm’s life-change. For these admirers, Malcolm’s truth-talk is not as important as the way he turned his life around, that is, from a street hustler and violent criminal (Detroit Red) to a civil rights leader and cultural icon (Brother Malcolm).

There is much debate as to whether Malcolm was this immense crime lord or, to put it another way, a scourge on society. Manning Marable’s controversial biography suggests that Malcolm’s criminal background was embellished to make the story of his conversion more alluring. And even if that is the case, the story of his turnaround—his religious conversion—is still extraordinary. Think about it. He was a man so antireligious that, while in prison, his cellblock called him “Satan.” And yet, before being released, he turns around and becomes a committed yet, before being released from prison, he was educated—even more impressive, a self-educated—man. He read classic philosophers, such as Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, and Kant; he read American history; he read the theologies and religious histories of the major world relgions, not just Islam. And not only did he read all of this, but he could debate these topics as well. That’s a great story!

The significance of Malcolm X’s fearless oratory and his exceptional conversion cannot be overstated. Unfortunately, there is an often neglected theme in The Autobiography of Malcolm X. Maybe it’s not as sensational as some of the abovementioned details or some other elements of the autobiography. But, in my humble opinion, the most impressive and inspiring part of Malcolm X’s story is this: he found his purpose…and his purpose was his people. There’s a line from the autobiography that pretty much sums up his purpose. It’s when he says, “you will never catch me with a free fifteen minutes in which I’m not studying something I feel might be able to help the black man.” Everything Malcolm X did, the way he went about studying not just books but all that impacted the lived experience of black people, was about his people. And nothing—absolutely nothing—diverted him from this purpose. When the Honorable Elijah Muhammad, the man whom Malcolm believed had saved him, would not become politically involved to make the lives of black people in American better, he sought out a religion that would help him accomplish his purpose. This purpose always left him open and ready for what he called “change and action” for his people.

With all that is going now, it seems that Malcolm X’s story is just as important today as it was decades ago. Most of us will never have a life-changing religious experience, at least not like Malcolm’s, and most of us will not turn ourselves into self-taught savants (who has time to read Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason anyway). All of us can find our purpose. That should be our story. And it would be great if, just like Malcolm, our purpose could be our people.

Staff Writer. J.P

Courtesy of; http://ineverknewtv.com/

Leave a Reply