(ThyBlackMan.com) The wildly popular movie, The Help, though hailed in many quarters is at the same time roundly condemned in others. Why is that. . .

Every movie, in fact anything that calls itself art, operates on two levels. There is what you see and hear, and there is what you do not see and do not hear, but pick up nonetheless on the symbolic, that is, the unconscious level.

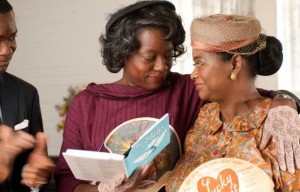

One of the heroines of the movie is an older Black woman who works as a maid, the other is a well-to-do young white woman. They live in Jackson, the capital of Mississippi, at the height of the civil rights movement. The film depicts this young white woman as secretly recording the true life stories of Black maids who have taken care of generations of white families.

As the Black woman first begins to tell the white woman the story of her life as a domestic, the clock on the wall shows that it is seven minutes after seven. She says she was born in 1925, and began taking care of white families at 14. Note, 7 + 7 = 14. Also, 25 can be seen as 2 + 5 = 7. Seven is the lucky number in gambling, and overall it carries the connotation of good luck. The Black maid is taking a deadly gamble by opening up about the horrors she has experienced, but all these “7”s foreshadow that she’ll prove lucky and survive the dangers she is exposing herself to.

The over-riding, over-arching theme of the film is suffering, suffering and self sacrifice for the well being of others. The Black maids sacrifice their lives with their own families to make money to take care of their families by taking care of white families. During the course of the film, the real life head of the NAACP in Mississippi, Medgar Evers, is shot to death in Jackson, Mississppi. Also, President Kennedy is assassinated. These men are seen as Christ figures. And the Black maid’s own son, as she tells the white woman, was gravely injured by whites and left to die.

In the kitchen of the maid’s home, where the two women sit as she recounts her tales, there is a picture of her son and picture of a white Jesus. When Kennedy is killed his picture is added to the pantheon thereby making it a trinity.

After many twists and turns the white woman finishes writing her book, and publishes it. Once it comes out the Black maid is hailed as a hero when she comes to church. Look carefully at the Black minister who welcomes her, and you will clearly see that he is clutching a church fan over his chest and on the fan is the same picture of the white Jesus that is on the wall of her kitchen.

Later, the maid is faced with prison for speaking out. However, the young white woman and her own mother come to the Black woman’s defense. Also, the white woman shares her royalty check equally with all the maids who helped her. Thus, the movie states, she has to divide it into 13 parts. Note, Christ, the “Savior” had 12 Apostles. So he and his followers also numbered 13 in all.

Early in the film, the young white woman says that Margaret Mitchell, author of Gone With The Wind, fostered the Mammy stereotype, that of the always faithful Black female servant. She declares that she intends to tell the true stories of Black servants. Does she?

Yes, she does, in the film. But the film is fiction. Yes, a book was written about the travails of Black maids working for rich white families in the Deep South. But it was written in 2009, not in 1963 at the height of the civil rights movement as shown in the film. And did the real life author share her proceeds with the women whom she chronicled? One is suing her for defamation of character.

Is the film, nonetheless, representative of the good white people of the South who came out and stood up for African Americans during the civil rights movement? Yes, white women and men worked and died in the movement, but didn’t they come from the North? In fact, when Martin Luther King was put in jail in Birmingham, Alabama for leading a series of demonstrations, eight leading white clergymen fromBirmingham wrote him a carefully thought out letter proclaiming that they sympathized with his cause, but that he needed to be patient and fight the struggle in the courts, not in the streets. King’s masterful response, Letter From A Birmingham Jail, is a classic in the annals of American history.

Note how the author within the movie says she is trying to overturn Margaret Mitchell’s Mammy stereotype, but the real author actually furthers it by showing whites as the saviors that they were not, and by having one of the maids say, “Frying chicken tends to make you feel better about life. I love me some fried chicken!” Meanwhile, Dreamworks, the company that made the film, in association with Home Shopping Network is now selling a line of frying pans, and assorted cookware, what it calls “one of a kind items inspired by” The Help.

Yes, yes, yes. It is a fictional film, not a documentary. It is, after all, only a movie. But it is also something else. It is a work of art. And like every work of art, it needs, in fact it demands, a critique. This was mine.

Staff Writer; Arthur Lewin

This talented writer has also self published a book which is entitled; Read Like Your Life Depends On It.

Thank you, Nicholas, for bringing this to our attention. From what I have been able to find out about Morris Dees he seems to be a great fighter for civil rights. However, this film was set in the year 1963 in Mississippi, and I noted that those whites deeply involved in the civil rights movement at that time, as far as I could tell, came from the North.

The earliest civil rights suit I can find Dees being involved in was in 1969, five years after the passage of the Civil Rights Act and four years after the Voting Rights Act. This is not to take anything away from Mr. Dees. This is only to say, again, “if you can cite white individuals in the Deep South during the height of the civil rights movement who stood up against Jim Crow, please let me know.”

I hope that you can, and I will trumpet them. Please note that I never got into this discussion to bash any group of people. And I never called the author of the Help a racist. All I said was that her book, and the movie, gave a misleading impression of American history.

I cite Morris Dees, Southern Proverty Law Center, he is clearly white and Southern, born Alabama 1939, University of Alabama Law school 1960. He has arguably stood against Jim Crow.

Me, one can go through life just looking at the surface, or one can choose to look beneath. Many people think, for example, that a dream is just a dream, but psychiatrists understand that anything the mind constructs reveals hidden information about that mind. I think that psychologists are right.

Take your letter for example, you said that I said all white people are racist. I did not. I said, “Yes, white women and men worked and died in the movement, but didn’t they come from the North?” And note I posed it as a question. So if you can cite white individuals in the Deep South during the height of the civil rights movement who stood up against Jim Crow, please let me know.

I also noticed that you begin your comments with, “You people.” And of course I should not read anything into that. Doubtless, you are a fair minded objective individual. But if you are why did you say that I said all white people are racist when clearly I did not?

Wow. You people can find subliminal messages in anything, can’t you? Seriously, the book is fiction. Furthermore, it was meant to entertain, not persuade or be used as a historical reference. Really, I found both the book and the movie quite entertaining. I might have given more credit to your article if you hadn’t started with the sevens bit. I highly doubt that the number had any significance. If a four year old child were to die in a movie, would you jump to the conclusion that, because the Chinese word for ‘four’ sounds like ‘death,’ she was destined to die? Of course not. That would just be absurd.

Furthermore, in case you didn’t notice, it wasn’t a ‘white heroism’ story. As you might remember, the main villain (Hilly Hollbrook) was white. And only one of the three main heroines were white. Really, isn’t saying that ‘all whites hate African Americans’ more racist than a book having a white character stand up against prejudice in defense of an African American character? In other words, you’re saying that it’s racist for there to be a white person standing up against racism, but it’s not racist for you to say that all whites hate blacks. Yep, that makes a lot of sense to me.

Yes, it is. It is the latest in a long line of films stretching back to Tarzan.

“Meanwhile, Dreamworks, the company that made the film, in association with Home Shopping Network is now selling a line of frying pans, and assorted cookware, what it calls “one of a kind items inspired by” The Help.”

Wow! That’s interesting.

I have yet to see the movie. I however, wonder if this was another movie about white folks saving the day. I’ll have to watch the movie and read the book first before offering my opinion.

This message is for md: “Most movies are political”. Believe me, the Jewish people know it. You will never see in a film one of them in prison with a kipa. It is time that our people wake up and smell the coffee by ending to be modern minstrels.

Thank you. Yes, the same is also true of Dances With Wolves, The Last Samurai, The Matrix, etc. Maybe we should discuss Avatar next.

I had the same thoughts about Avatar, which seemed to mirror the confrontation between whites and Native Americans. The fact that it was a human who saved the natives in Pandora from being conquered by his own people created an undertone of paternalism in that the savior came from the would-be conquerors. Beautiful movie and a great story, but there was that strange dynamic to it that you describe.

I haven’t seen The Help yet so I can’t comment on specifics, but I get you.

Brother Willis, I tried to be objective and stick to the facts. I do not believe this film to be historically correct. The South may have come a long way, but during the battle over integration, they way I remember it, local whites in the Deep South did not confront segregation. If I am shown to be wrong, then I will stand corrected. People are certainly free to make up stories about the past as are we to point out where they deviate from fact.

So what is your critique, Arthur Lewin? You leave a lot of open questions, and don’t definitively say what you think. You did a synopsis, not a critique. Do you think we need to support a movie like this? Or do you think it was entertaining or historically correct?

And you are clearly a gentleman and a scholar who believes in reasoned discourse.

The book is fiction. The movie is fiction. You promote racism by finding symbolism that only exists in your mind. You are a conspiracy theorist and an idiot.

Thanks, Dell. Yes. I too would like balance. Have you seen Sidney Poitier’s 1971 film, Brother John? He takes his earlier, In the Heat of The Night, to an entirely different level. I also highly recommend Sugar Cane Alley (1987) and Burn (1966).

Solid article Author. Somebody else said it before, and I will echo it because I felt the same way. I call it the Mississippi Burning syndrome where whites save us ‘po black folks’. There always seems to be an over valuing of white heroism an and undervaluing of Black heroism in our struggles. I would be cool with a balance.