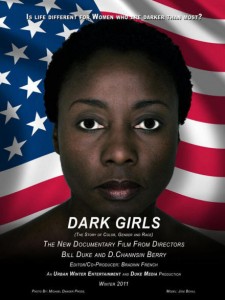

(ThyBlackMan.com) “Healing starts when you create dialogue.”- Bill Duke at the Apollo premiere of Dark Girls1/13/12

On Friday, January 13, 2012, Dark Girls: The Movie premiered at the Apollo Theater in New York City. Here I offer a review of the film and its implications for its intended audience, women of color.

Colorism in a nasty little word that many in the black community don’t want to acknowledge, though willingly engage in perpetuating its existence. Colorism is defined as discrimination in which individuals are treated differently based on their skin color. This affects one’s employment opportunities, likeliness of incarceration and contributes to a social stigma  that is widely accepted. Listen to contemporary urban radio stations, scan social media or watch music videos: the dark skin-light skin dichotomy is there. Possessing light skin is held in high regard while being dark skinned is seen as a hindrance–if you let the media tell it. Young black girls of all hues are bombarded with images and rhetoric on daily basis that serve to chip away at their self esteem and sense of self worth. When ingesting lyrics such as Lil Wayne’s “beautiful black woman, I bet that b*tch look better red,” I wonder, how much of an impact does this have on these girls? Are they internalizing this message of superiority/inferiority based on skin complexion?

that is widely accepted. Listen to contemporary urban radio stations, scan social media or watch music videos: the dark skin-light skin dichotomy is there. Possessing light skin is held in high regard while being dark skinned is seen as a hindrance–if you let the media tell it. Young black girls of all hues are bombarded with images and rhetoric on daily basis that serve to chip away at their self esteem and sense of self worth. When ingesting lyrics such as Lil Wayne’s “beautiful black woman, I bet that b*tch look better red,” I wonder, how much of an impact does this have on these girls? Are they internalizing this message of superiority/inferiority based on skin complexion?

Dark Girls, a documentary produced by Bill Duke and D. Channsin Berry, hopes to deliver a different message to young black girls. This message, one of healing, acceptance and pride in one’s appearance, hopes to counter the mainstream depiction of women of color. Duke and Berry are currently embarking on a national screening tour of the film, which is followed by a 30 minute Q&A session afterwards. The film was well received by the Apollo audience, but will the message be received by the ones who need it most? The film is rather engaging, featuring interviews from psychologists and people from the entertainment industry, notably Michael Colyar and Viola Davis. There’s also anecdotes from black women who discuss their experiences as “dark girls,” black men who either profess love or disdain for dark skinned women, and a couple of white men who are married to dark skinned black women (we’ll get to this later).

There are eight segments to the film in which colorism is dissected: History, Impact, Family, Men: On Women, Women: On Men, Global, the Media, and Healing. In examining the issue on a global scale, the film offers the statistic of $43 billion dollars in sales for skin bleaching products in 2008. There’s also a young Korean woman who discusses visiting Korea as a young child, being considered dark (though her skin tone is that of Mariah Carey) and treated differently. Though she stated that she was from California, it wasn’t made clear whether she was mixed or not. It’s interesting to note that this particular segment was not well received by the audience; a lot of teeth sucking went on at this point. In the Men: On Women segment, many black men shared sentiments that either echoed popular media or made reference to black women being queens who should be held in the highest regard. Many of the black women interviewed expressed pride in seeing Michelle Obama in the White House. Most of the information in the documentary is not new for someone like me, who studies issues of gender, race and class on a daily basis. However, it is somewhat of a catharsis to see these stories told on a much larger platform than what we are accustomed.

With that being said, the film is not flawless in its execution. I raised my eyebrows at a few segments, two of which I will discuss in depth below:

In one scene, a black woman shares that she believes that the white man reveres black women, and that that black man’s reverence of the black woman is more paternalistic, not viewing the black woman as a goddess, per se. This sentiment was subtly echoed at a few different points throughout the documentary, especially when the two white men were gushing over their wives and their innate attraction to women of color. There was yet another scene in which an older Black woman discusses traveling abroad and having her deep brown complexion embraced by whites more than it has ever been by blacks. Wait. Was it not whites who historically created this whole color chasm or did we as people of color automatically do it to ourselves? It seems as if the omnipotence of racism (of which colorism is a by product) was ignored in order to fit in with the agenda of the film. This is something that I can’t overlook and gingerly accept for the sake of empowering my sisters. If we are going to paint a picture, don’t neglect to give full attention to detail. There are white men who genuinely love black women. Got it. But there are also white men who have a perverse attraction to Black women for distasteful purposes. Some of the Black men in the film share that they only desire dark skinned women for sexual purposes. Are we to believe that white men only intend to love us wholly for who we are? If so, Hottentot Venus would not have been on display as a “wonder” at European circuses, and the Mammy, Sapphire, Jezebel images wouldn’t exist.

During the Q&A session, a member of the audience made a statement to the producers that I wholeheartedly agreed with: “I don’t want people to walk away with the notion that to empower dark skinned women, you must vilify light skinned women.” At some points in the film, it did feel like this tension was encouraged through certain comments from the interviewees. In response to her statement, Duke replied that the film continuously tells Black women of all hues that we are in this together. He also mentioned that he and Berry are working on a film that examines the ordeals of light skinned black women titled “The Yellow Brick Road.”

Where Do We Go From Here?

Healing is the objective. But how can one undo hundreds of years of this psychological processing? As stated in the film, “you have to be taught to discriminate against skin color.” It doesn’t casually happen. Young black girls and boys are taught varying degrees of color preference at home, in school and via media outlets. Many of the interviewees in the film discussed their healing process as tapping into their own inner strength after years of battling with an inferiority complex due to their skin tone. One psychologist remarked that in the Black woman’s quest for healing from such negativity, “you can’t depend on a Black man to liberate you from that.” Another participating psychologist in the documentary offered this charge: society perpetuates colorism and has a responsibility to self correct. True. Where should we begin? Having the conversation is a good start.

Staff Writer; T.S. Taylor

Feel free to also connect with this sista via Twitter; ProfToniBK.

Leave a Reply