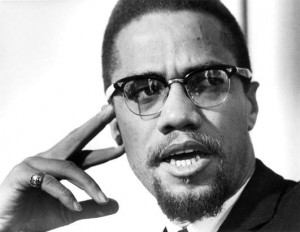

(ThyBlackMan.com) I recently read about historian and scholar Manning Marable passing away, just days before the publication of his controversial book, “Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention.” The book has ignited a firestorm of commentary, which is not surprising.

The coverage took me back to when I was a teenager in New York in the 1960s when Malcolm was holding Harlem rallies in front of Micheaux’s  National Memorial African Bookstore. Saturdays, when I worked in my father’s grocery store in New Rochelle, the radio would be tuned to Malcolm’s rally. I vividly recall a broadcast in which Malcolm described Black separatism and how the Black man was like strong black coffee; and when you add milk to coffee, it weakens it.

National Memorial African Bookstore. Saturdays, when I worked in my father’s grocery store in New Rochelle, the radio would be tuned to Malcolm’s rally. I vividly recall a broadcast in which Malcolm described Black separatism and how the Black man was like strong black coffee; and when you add milk to coffee, it weakens it.

Respected his call

My father would buy a Muhammad Speaks newspaper every Saturday and give the Muslim brothers a space in his store to sell their bean pies. My dad understood the importance of not relying on anyone –– except perhaps his family – to achieve his goals.

Malcolm’s Black Nationalist rhetoric did not strike a chord with my teenaged self. It made me uncomfortable – maybe because what he was saying was too close to some truths I was just beginning to take in. I had dismissed him as a hotheaded radical who chided the leaders of the civil rights movement as being Uncle Toms because of their more measured approach to breaking down barriers.

As I matured and learned more, I began to appreciate the Malcolms and the Martins. I also discovered that sometimes what you read is not necessarily how it really is. The media had set Malcolm and Martin against each other – the raving radical and the peaceful preacher. It sold newspapers and increased Nielsen ratings.

Opened up

Malcolm X voiced his disapproval of the integrationist philosophy of the civil rights movement, but he did become more open in later years, especially after his break from the Nation of Islam and his journey to Mecca in April 1964.

Prior to that, there was evidence of Malcolm’s expanding perspective when he reached out in a letter to Whitney Young of the Urban League. Dated July 31, 1963, Malcolm invited Young and Black leaders including Dr. King, U.S. Rep. Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., James Farmer, A. Philip Randolph, Ralph Bunche, James Forman and others to speak at a Harlem rally in August. The purpose was to form a “United Front.” Malcolm urged the leaders to “submerge our ‘minor differences’ in order to seek a common solution to a common problem posed by a common enemy.”

Almost a year later, he sent Dr. King a telegram while MLK was jailed in St. Augustine, Fla. for attempting to integrate a Whites-only motel and restaurant. Malcolm wrote, “We have been witnessing with great concern the vicious attack of the white races against our poor defenseless people there in St. Augustine. If the Federal Government will not send troops for your aid, just say the word and we will immediately dispatch some [of] our brothers there to organize self-defense units…”.

More to come

Writers and historians will be revisiting and revising the narrative of Malcolm X’s life as more research is made available through his personal papers, undiscovered archival material, and accounts from new sources. It is up to each of us to read carefully these accounts and take from them what we can.

Malcolm X’s contribution to the history of Black America is immeasurable. Revisions to Malcolm’s personal history may be interesting, but it should not detract from his legacy. What matters is Malcolm’s tremendous personal sacrifice, his advocacy of self-determination for African-Americans, and his fight for global human rights.

Written By Linda Tarrant-Reid

Leave a Reply