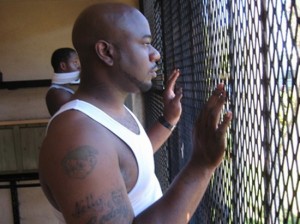

(ThyBlackMan.com) Mass incarceration has not reduced crime, but it has made prison a more common experience for poor black men than joining a union or doing military service…

For decades now, America has been pursuing a deeply punitive anti-crime social policy: the criminal-punishment binge. It is what lies at the root of the heavy overrepresentation of blacks — and increasingly, Latinos — in our nation’s jails and prisons. Our only hope of creating a fair and equitable criminal-justice system is to turn away from the false belief that punishing more people at ever-younger ages, for longer periods of time and for an ever-widening array of infractions is the only sensible response to the problem of crime.

The rise in incarceration has largely been driven by social policy — not by changes in the amount or severity of crime. The strategy was advanced under many slogans, from restoring law and order to our streets, to getting  tough on crime, to waging a war on drugs, to turning out of elective office anyone who might be seen as “soft on crime.”

tough on crime, to waging a war on drugs, to turning out of elective office anyone who might be seen as “soft on crime.”

The policy tools attached to this binge include mandatory minimum sentences, truth-in-sentencing guidelines, sentencing enhancements for various offenses, crack-versus-powder-cocaine sentencing differentials, the federalization of many of what were once only state criminal offenses, trying juveniles as adults, three-strikes-and-you’re-out provisions and greater availability of the death penalty.

The result is an epic expansion of our reliance on jails and prisons as the response to crime, so much so that the U.S. is now the world’s leader at incarcerating its own citizens. As the title of a 2008 Pew Charitable Trust report (pdf) put it, one in 100 Americans is now behind bars. This shocking declaration was surely emphasized by the report authors in order to jar us into considering the enormous waste of dollars and human lives that the new mass-incarceration society entails.

And we know something else: The rise of mass incarceration has had a disproportionate effect on African-American communities, especially those that are low-income. The one-in-100 stat increases to one in 31 for Americans who are under some form of criminal-justice supervision (if you include those also on probation and on parole). For black Americans, however, that latter figure stands at a thoroughly depressing 1 in 18.

But it gets even worse. We are at a point where 1 in 15 black men is in jail or prison — and for those between the ages of 20 and 34, the rate is 1 in 9.

University of California sociologist Loïc Wacquant has labeled the situation a new fourth state of racial oppression. In the wake of the successive collapse of slavery, Jim Crow and then ghetto segregation as mechanisms of black oppression and white supremacy, we get what he calls the “carceral state,” or what legal scholar Michelle Alexander labels the “The New Jim Crow.”

For Some, Incarceration Becomes the Norm

I want to stress three points about racialized mass incarceration. First, incarceration is so extreme and so biased on the basis of class and race that prison has become an ordinary life experience for poorly educated blacks, in a manner not characteristic of any other segment of American society.

My Harvard colleague sociologist Bruce Western, in his book Punishment and Inequality in America, compared rates of incarceration for two generations of men: those born in the five years immediately following World War II and those born during the height of the Vietnam War era (1965 to 1969).

Black men in the post-World War II generation who did not graduate from high school had a less than one-in-five chance of going to jail or prison by the time they were 30 years old. Similarly educated black men born in the Vietnam era, however, had a three-in-five chance of spending some time in prison by the time they reached the same age. That is, nearly 60 percent of black men in this more recent cohort were destined for jail or prison — a figure that is sure to be worse for the most recent cohorts of poor and poorly educated black men.

This now means that exposure to jail and prison is a more common experience for a generation of poor blacks than is, say, membership in a labor union, service in the military or receipt of a variety of government benefits.

Prison Spending Skyrockets

Second, the growth in state expenditures on jails and prisons has far outstripped the growth in all other state expenditures, with the exception of Medicaid. A 2009 Pew Center on the States report estimates that, on average, it costs $29,000 a year to house each inmate. In 2007 we spent $49 billion on corrections overall (jails, prisons, and supervision of those on parole and probation). That figure, which is four times what it was a decade earlier, reflects growth over the decade of more than 127 percent in inflation-adjusted dollars.

Over the same time period, average spending on higher education rose by only 21 percent (one-sixth the growth in prison expenditures). Moreover, according to the Pew Report, in some states — including Connecticut, Vermont, Michigan, Delaware and Oregon — corrections spending actually exceeded spending on higher education.

In this era of profoundly constrained state budgets, it requires no great leap of logic or complex analysis to conclude that scarce state dollars are surely better invested in early-childhood-education programs and meaningful access to higher education than in building, staffing and filling more prison cells with inmates.

We Need a Smarter Approach to Crime Fighting

Third, the time has arrived to get smart on crime. The get-tough punitive agenda has arguably failed as a crime-fighting strategy and has deepened racial division and inequality in America. The best estimates suggest that as little as 5 percent of the decline in crime rates over the last decade-and-a-half can be attributed to the new mass-incarceration society.

What probably contributed more substantially was a combination of changing age distributions within the population, stabilization of the crack-cocaine markets and stigmatization of crack use, and a shift to community policing strategies.

We should be focused on decreasing the number of prison admissions, reducing the length of prison stays for those not involved in violent crime, and increasing the pressure on local and state governments to evaluate and intervene to change any policing strategy or adjudication practice that is producing racially disparate rates of official scrutiny, arrest and incarceration.

For the first time in more than 30 years, state prison populations have shown a slight decline. But the federal prison population continues to grow. And the heavily disproportionate incarceration of minorities, especially poor blacks, for low-level drug offenses continues largely unabated.

This punitiveness binge would never have gone on for so long or reached such extreme levels if those being swept up into the criminal-justice system weren’t largely black and poor. Whether you call it the carceral state, the fourth stage of racial oppression or the New Jim Crow, the situation is unacceptable.

Let us be the generation that decides to get smart on crime. Let us be the generation that undoes the connection between race and who populates our jails and prison. Let us break forever the shackles of racialized mass incarceration.

Written By Lawrence Bobo

Leave a Reply